The Supreme Court decision in Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968), dealt with a First Amendment challenge to Ohio election laws as they pertained to third-party candidates.

The Court held that the “heavy burden” placed on third parties by the law was discriminatory and violated the First Amendment’s right to free association and the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause.

Third-party candidates challenged Ohio’s ballot access rules

An Ohio election law made it more difficult for third-party candidates to get their list of presidential electors on the ballot by requiring that they have signed petitions from 15 percent of the voters in the prior gubernatorial election.

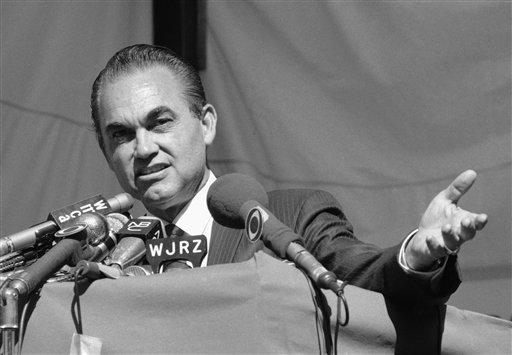

The American Independent Party, formed by supporters of presidential candidate George C. Wallace, had enough signatures but did not meet the deadline. The Socialist Labor Party, which had a candidate on Ohio’s ballot for the past 20 years, did not collect enough signatures.

A preliminary injunction had placed the names of Ohio American Independent Party electors — but not the Socialist Labor Party electors — on the ballot. Both parties challenged the Ohio election law as violating the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. A three-judge district court found that the laws were unconstitutional and ruled that the parties were entitled to write-in space but not ballot position. The Parties appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Independent Party immediately sought interlocutory relief from Justice Potter Stewart. Relief was granted to the party after a hearing in which Ohio declared the candidate could be placed on the ballot if there was not a long delay. Several days after that order, the Socialist Labor Party sought relief, but it was not granted because that party’s action was not timely enough to prevent disruption of the election.

Court said heavy burden on third-party candidates violated First Amendment

Writing for the majority, Justice Hugo L. Black denied that the issue was a political question but agreed that it involved First Amendment rights of association and the right to vote.

He thought the state had failed to establish a “compelling interest” for the heavy burden it placed on third parties. He observed that the Ohio system favored a two-party system and noted, “Competition in ideas and governmental policies is at the core of our electoral process and of the First Amendment freedoms.”

He agreed that the lower court had adequate reason for granting relief to the party that made the initial claim (the American Independent Party) and not to the second party (the Socialist Labor Party), which had not come to court in a timely fashion and for which a remedy might require designing new ballots at the last minute.

Concurring opinion said ballot law suffocated rights of association, voting

In a concurring opinion, Justice William O. Douglas argued that the “right of association is one form of ‘orderly group activity’ … protected by the First Amendment.” He further thought that “[c]umbersome election machinery can effectively suffocate the right of association, the promotion of political ideas and programs of political action, and the right to vote.” He agreed that the Socialist Labor Party had initiated its own action too late for it to receive declaratory relief.

Justice John Marshall Harlan II wanted to rest the decision solely on “the basic right of political association” as protected by the First Amendment as applied to the states via the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment rather than also involving the equal protection clause.

Three justices dissented, saying they would have upheld state requirements

Justice Potter Stewart dissented. He did not think that the precedents relative to the right of association mandated the majority decision in the case and thought that most of the effects on party participation in the electoral process that the majority had foreseen were speculative.

Justice Byron R. White wrote a partial dissent, arguing that the American Independent Party had not made an appropriate effort to comply with state requirements. Chief Justice Earl Warren also dissented, believing that the Court had rushed the case to judgment and had not given due consideration to state powers.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.