In Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951), the Supreme Court applied the clear and present danger test to uphold the convictions of 11 U.S.-based communists for their political teachings.

Dennis convicted of conspiring to form American Communist Party

Eugene Dennis and 10 other party leaders had been convicted of conspiring to form the American Communist Party, thereby violating the Smith Act of 1940, which made it a crime to “knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of over-throwing . . . the government of the United States by force or violence.”

The bitter and contentious trial, which lasted about nine months and was followed around the world, featured demonstrations, threats, and countless courtroom challenges by both sides.

Defense insisted that the defendants’ conduct did not pose ‘clear and present danger’

Defense counsel insisted that the defendants’ teaching of and advocating communist doctrine could not possibly constitute conduct that posed a “clear and present danger” to the United States, referring to the test first enunciated in Schenck v. United States (1919), when the Court upheld the conviction of a draft protester during World War I.

At the trial’s conclusion, Judge Harold Medina instructed the jury members that they were not to deliberate on whether the defendants’ actions could possibly have caused harm to the nation. They were merely to decide whether the defendants had engaged in a conspiracy and would take steps to overthrow the government given the chance, as alleged by the federal prosecutors.

Judge Medina thus reserved to himself, and ultimately to Congress, the heart of the clear and present danger test: an inquiry into the nature of the conduct outlawed. The jury, after deliberating less than a day, returned guilty verdicts for all defendants.

When does conspiracy become ‘present danger’?

The convictions were upheld on appeal. Writing for the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Judge Learned Hand carefully explained the current First Amendment doctrine of clear and present danger. Referring to a concurring opinion in Whitney v California (1927), he discussed the lack of a fixed standard by which to determine when a danger is clear or how remote a danger may be and yet be called present.

According to Hand, the question was “how long a government, having discovered such a conspiracy, must wait” to act. “When does the conspiracy become ‘a present danger’?” He concluded, “In each case [the government] must ask whether the gravity of the ‘evil,’ discounted by its improbability, justifies such invasion of free speech as is necessary to avoid the danger.”

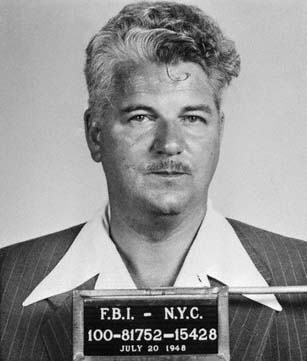

The convictions of seven Communist leaders in the photo above,, along with four others not pictured, were upheld in 1951 by the Supreme Court in Dennis v. United States. Pictured from left are.John B. Williamson, Harry Winston, John Gates, Benjamin J. Davis, Jacob Stachel, Gus Hall and Eugene Dennis. The leaders had been convicted of conspiring to form the American Communist Party, thereby violating the Smith Act of 1940, which made it a crime to “knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of over-throwing . . . the government of the United States by force or violence.” (AP Photo/Jacob Harris, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court looked at whether Smith Act violated First Amendment

The Supreme Court limited its review of this decision to two questions: whether the Smith Act as written or as applied was contrary to the First Amendment protection of freedom of speech, and whether the statute was so vague as to violate the First and Fifth Amendments.

There was no majority opinion. Chief Justice Frederick M. Vinson’s plurality opinion, joined by Justices Stanley F. Reed, Harold H. Burton, and Sherman Minton, was based in its entirety on Hand’s analysis.

Vinson began with his own explanation of the meaning of “clear and present danger” but finally simply adopted the “gravity of the evil” test, adding little beyond the rhetorical flourish that “the words cannot mean that before the Government may act, it must wait until the putsch is about to be executed, the plans have been laid and the signal is awaited.” He dispatched the issue of the vagueness of the Smith Act in two short paragraphs at the end of the opinion.

Justices Felix Frankfurter and Robert H. Jackson joined Vinson and concurred in the result. Frankfurter’s opinion relied heavily on his preference for judicial deference to the legislature.

Justice Jackson said no right to ‘gang up’ on government

Jackson’s concurrence stressed the inadequacy of the clear and present danger test in dealing with worldwide conspiracies such as communism. He said the standard was more appropriate for street corner disputes than ideological causes. In an eloquent opinion, he wrote that there “is no constitutional right to ‘gang up’ on the Government.”

In a brief and pointed dissent, Justice Hugo L. Black argued that the law on its face and as applied in this case was nothing more than a prior restraint on speech and press forbidden by the First Amendment.

Justice William O. Douglas’s dissent stressed that the defendants were being prosecuted for teaching and advocating from books that were not themselves banned. He concluded that the government was punishing the communists for their beliefs rather than their advocacy.

Dennis has not been overruled, but its strength has been diluted by subsequent cases — most notably Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) — which have both limited the scope of its holding and substituted a standard of imminent lawlessness for the gravity of the evil test.

This article was originally published in 2009. James L. Walker (1942-2019) taught political science at Wright State University for 33 years.