James Madison’s “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments,” a document presented to the Virginia General Assembly in 1785, argued for complete religious liberty and against government support of religion in any form.

“Memorial” reveals Madison’s started Virginia on a path to religious freedom

Madison’s target was an assessment bill that would have imposed a general tax on Virginians to pay “teachers of the Christian religion” a modest salary. His efforts not only helped defeat the bill, but also created a political climate in Virginia that enabled him to secure passage the next year of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, the first unreserved guarantee of religious liberty and full separation of church and state in U.S. history. The “Memorial” also reveals Madison’s thinking about religious freedom four years before he introduced a national Bill of Rights in 1789.

The Anglican Church was the established church of Virginia

The Anglican Church had been the established church of Virginia since 1606 and the privileged recipient of public funds. Dissenters were subject to franchise restrictions and sometimes harsher penalties. By the eve of the Revolutionary War, however, the church had lost many parishioners to dissenting churches and was suffering financial hardship.

In his home state of Virginia, Madison had been an early and forceful advocate of religious liberty and an opponent of religious establishments. In June 1776, he served on a committee charged with preparing a Declaration of Rights to be included in Virginia’s new constitution. The chair of the committee, George Mason, had prepared a draft that spoke of “the fullest Toleration in the Exercise of Religion.” Madison successfully moved to amend the declaration to remove the word ”toleration,” which suggested a second class status for dissenters, and instead to declare “that all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience.”

Madison was unsuccessful, however, in securing acceptance of his proposal that “no man or class of men ought, on account of religion to be invested with peculiar emoluments or privileges,” which would have clearly prohibited any religious establishment in Virginia.

Virginia bill would have required taxpaers to support a Christian church

The assessment bill introduced in the Virginia General Assembly in 1784 would have required all taxpayers to “pay a moderate tax or contribution annually for the support of the Christian religion, or of some Christian church.” The bill would not have established any particular Christian denomination (all Christian denominations were eligible for the funds) and did not penalize anyone for failing to believe in or to practice Christianity.

Sponsored by Patrick Henry, a hero of the colonial resistance, the bill was supported by many influential Virginians. Richard Henry Lee argued that religion, as “the guardian of morals,” must be protected from the “avarice” that would destroy religion “for want of legal obligation to contribute something to its support.”

Madison considered the bill a violation of religious liberty

Madison, however, considered the bill a “dangerous abuse of power” and a direct violation of the guarantee of religious liberty in the Virginia Declaration of Rights. A mild religious establishment was still an establishment: “Distant as it may be in its present form from the Inquisition, it differs from it only in degree.”

Many of Madison’s arguments in the “Memorial” closely followed those of John Locke’s in “A Letter Concerning Toleration” (1689). But Madison was arguing for a much wider range of religious freedom and a much more complete separation of church and state than anything Locke had envisioned.

Madison argued religion must be left up to the individual

Madison’s fundamental argument was that religion “must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man,” because it depended on “the evidence contemplated by their own minds” and “cannot follow the dictates of other men.” For that reason, religious conviction was an inalienable right over which no government, including government based on majority rule, could have legitimate power. The bill falsely presupposed “that the Civil Magistrate is a competent Judge of Religious Truth,” and that the same illegitimate authority used to “establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other Religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other sects.”

Moreover, Madison argued, Christianity flourished best without the support of government. Religious establishments bred “pride and indolence in the clergy,” and the assumption that Christianity could not survive without the patronage of government was “adverse to the diffusion of the light of Christianity.”

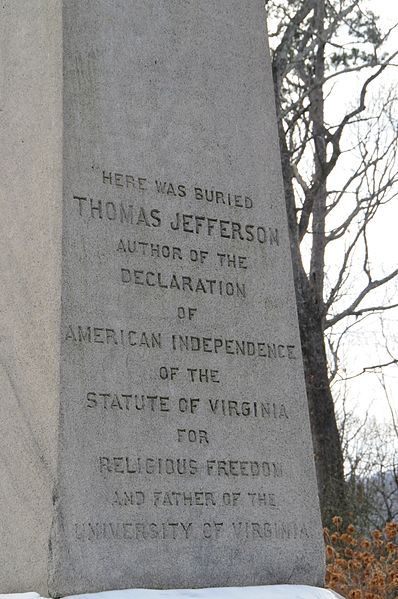

Madison used the political momentum of the Memorial and Remonstrance to secure passage in 1786 of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, originally drafted by Thomas Jefferson, who in 1786 was serving as a diplomat in France. Madison wrote to Jefferson that passage of the bill has “extinguished forever the ambitious hope of making laws for the human mind.” Jefferson had the bill listed on his tombstone as one of the three great accomplishments of his life. (Pictured here, via David Broad, CC BY 3.0)

Madison argued that religious freedom was a fundamental principle of the Revolution

Finally, Madison contended that the right of free exercise of religion “is held by the same tenure with all our other rights.” If legislators were given power to control religious belief, they may equally control the press or abolish the right of trial by jury or even “erect themselves into an independent and hereditary Assembly.” To give government any authority over religion violated the fundamental principle of the American Revolution: “It is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties. We hold this prudent jealousy to be the first duty of Citizens, and one of the noblest characteristics of the late Revolution.”

The bill was defeated

Madison’s ”Memorial” was widely circulated throughout the state, and with the support of Baptists and Methodists, who distrusted religious establishments from long experience, the assessment bill was defeated. Madison used the political momentum of the assessment contest to secure passage in 1786 of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, originally drafted by Thomas Jefferson, who in 1786 was serving as a diplomat in France. Madison wrote to Jefferson that passage of the bill has “extinguished forever the ambitious hope of making laws for the human mind.” Jefferson had the bill listed on his tombstone as one of the three great accomplishments of his life.

This article was originally published in 2009. James H. Read is Professor of Political Science at the College of St. Benedict and St. John’s University of Minnesota. He is the author of Power versus Liberty: Madison, Hamilton, Wilson, and Jefferson (2000) and Majority Rule versus Consensus: The Political Thought of John C. Calhoun (2009), as well as several articles and book chapters in the field of American political thought. He is currently writing a book titled Sovereign of a Free People: Abraham Lincoln, Majority Rule, and Slavery.