Overbreadth is shorthand for the overbreadth doctrine, which provides that laws regulating speech can sweep too broadly and prohibit protected as well as non-protected speech. A regulation of speech is unconstitutionally overbroad if it regulates a substantial amount of constitutionally protected expression. Overbreadth is closely related to its constitutional cousin, vagueness. A regulation of speech is unconstitutionally vague if a reasonable person cannot distinguish between permissible and impermissible speech because of the difficulty encountered in assigning meaning to language.

What’s behind overbroad regulations of speech

At least three motives drive the government’s impulse to fashion overbroad regulations.

- First, officials may employ overbroad regulations to suppress a broad range of criticisms directed against those in power.

- Second, officials may selectively enforce broad regulations to protect or suppress communicative content as they choose.

- Third, governments may adopt broad regulations to avoid judicial determinations of content or viewpoint discrimination.

Judicial examination of free speech regulations reflects an enduring concern: that free expression needs “breathing space” to survive (City of Houston v. Hill [1987]).

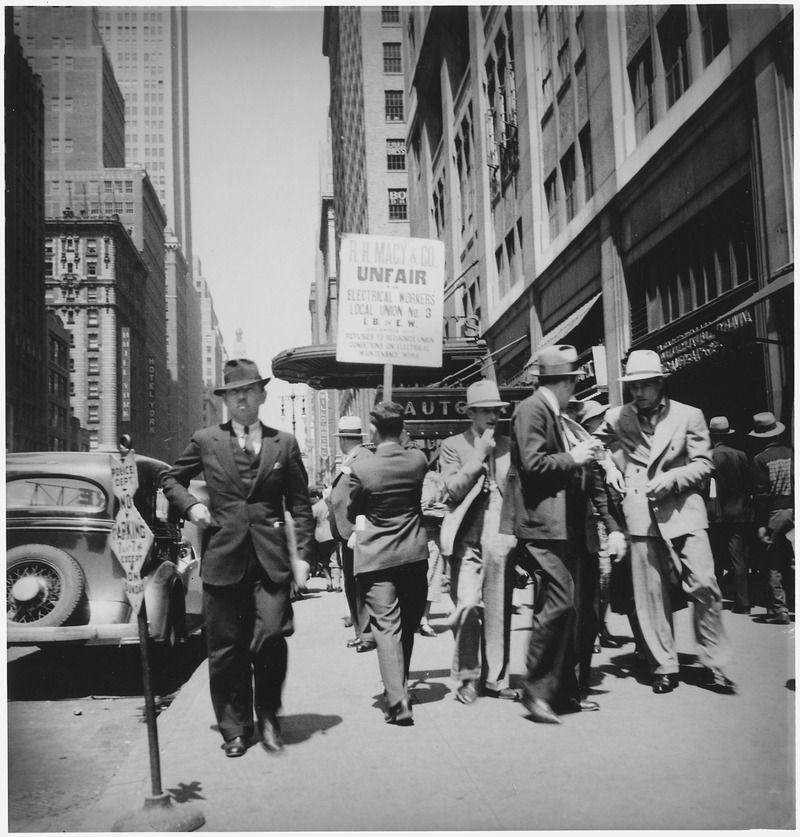

The Supreme Court implicitly recognized overbreadth in two 1940 decisions. In Thornhill v. Alabama (1940), the court overturned the application of a wholesale ban on labor that outlawed “peaceful and truthful discussion of matters of public interest” and violent actions alike. In Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940), the court held that a “breach of the peace” statute could not be broadly construed to “suppress free communication of views, religious or other, under the guise of conserving desirable conditions.” However, in both cases the court refrained from invalidating the statute in question, calling instead for a limiting construction of its applications.

The overbreadth doctrine remains a chief tool of constitutional litigators in First Amendment cases. For example, the court invalidated a law that criminalized lying about earning military honors in United States v. Alvarez (2012). Pictured here, Doug Sterner, whose research led to law, said it was meant to expose phony medal winners. (AP FILE Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Overbreadth doctrine considers ‘chilling effect’ of speech

The court emphasized in Broadrick v. Oklahoma (1973) that the overbreadth doctrine is “manifestly strong medicine” to be employed “sparingly and only as a last resort” and not in situations in which “a limiting construction has been or could be placed on the challenged statute.”

The court has also said overbreadth “must be not only real, but substantial as well, judged in relation to the statute’s plainly legitimate sweep.” This determination entails balancing the potential harm to society when unprotected speech goes unpunished against the societal implications of silencing communicators. As the court ruled in Gooding v. Wilson (1972), these implications include leaving grievances to fester and foisting the “chilling effects” of regulation upon those whose speech is protected by the Constitution.

Precisely because of these chilling effects, the overbreadth doctrine permits those to whom the law constitutionally may be applied to argue that it would be unconstitutional as applied to others. This doctrine constitutes an exception to the traditional third-party standing rule. However, in a series of recent cases, including Hill v. Colorado (2000), the Supreme Court implied that only parties whose speech is unprotected may facially challenge regulations on overbreadth grounds, a development that would alter the historical development of overbreadth doctrine.

Court strikes down law against lying about military honors

The overbreadth doctrine remains a chief tool of constitutional litigators in First Amendment cases. The U.S. Supreme Court continues to invalidate laws based on the overbreadth doctrine. For example, the court invalidated a law that criminalized lying about earning military honors, called the Stolen Valor Act, in United States v. Alvarez (2012). Similarly, the court struck down a federal law that criminalized the dissemination of materials depicting animal cruelty in United States v. Stevens (2010). The court reasoned the law was overbroad because it could be applied to hunting videos.

In 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court pushed back on overbreadth arguments when it upheld the conviction of a man who had promised immigrants a path to citizenship through a phony adult option scheme. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals had ruled as unconstitutionally overbroad under the First Amendment a federal statute that prohibited “encourag[ing] or induc[ing] an alien to come to, enter, or reside in the United States, knowing or in reckless disregard of the fact that such [activity] is or will be in violation of law.” But the Supreme Court disagreed in U.S. v. Hansen, saying that to “justify facial invalidation, a law’s unconstitutional applications must be realistic, not fanciful, and their number must be substantially disproportionate to the statute’s lawful sweep.” The court also said the context of the statute supported that it was only to be applied in the context of criminal activity.

In a concurring opinion in Hansen, Justice Clarence Thomas questioned the constitutionality of the overbreadth doctrine, saying that it simply “offers a license for federal courts to act as ‘roving commissions assigned to pass judgment on the validity of the Nation’s laws.’” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson dissented, saying that the majority ruling simply retrofitted problematic language in the statute, which discourages Congress from passing narrowly tailored laws in the first place.

This article was originally published in 2009 and last updated in 2023. Richard A. “Tony” Parker is an Emeritus Professor of Speech Communication at Northern Arizona University. He is the editor of Speech on Trial: Communication Perspectives On Landmark Supreme Court Decisions which received the Franklyn S. Haiman Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Freedom of Expression from the National Communication Association in 1994.