The Anti-Federalists opposed the ratification of the 1787 U.S. Constitution because they feared that the new national government would be too powerful and thus threaten individual liberties, given the absence of a bill of rights.

Their opposition was an important factor leading to the adoption of the First Amendment and the other nine amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights.

The political split between Anti-Federalists and the Federalists began in the summer of 1787 when 55 delegates attended the Constitutional Convention meeting in Philadelphia to draw up a new plan of government to replace the government under the Articles of Confederation. The Articles of Confederation was created by the Second Continental Congress and ratified by the states in 1781. The delegates in 1787 had decided to draw up a new plan of government rather than simply revise the Articles.

The Articles had created a confederal government, with a Congress with limited authority and states retaining primary sovereignty. The proposed new Constitution created a federal government in which national laws were supreme over state laws and in which the government could act directly upon individuals. Whereas the Articles had a single branch of government concentrated in a unicameral (one house) Congress in which each state had an equal vote, the new Constitution provided for three independent branches with a bicameral Congress in which one house was represented according to population.

New constitution was not prefaced with declaration of rights

The new constitution primarily attempted to protect liberties against this more powerful government through a system of separation of powers, federalism and other checks and balance. Although it contained some explicit prohibitions, such as those on the states in Article I, Section 9, and those on the states in Article I, Section 10, it was not, like many state counterparts, prefaced with a declaration or bill of rights such as the Virginia Declaration of Rights that George Mason had authored.

Whereas the Articles had required unanimous state legislative consent to amendments, the new constitution provided that it would go into effect when ratified by 9 or more of the 13 states. Moreover, it provided that such ratification would be conducted by special state conventions rather than by existing state legislatures. Once ratified, the document could be amended by a special convention called by Congress at the request of two-thirds of the states or by amendments proposed by two-thirds majorities of both houses of Congress, which were subsequently ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures or by specially called state conventions.

Some delegates thought changes to federalist government too radical

From the outset of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, there were delegates who thought that these changes were too radical. Some delegates such as John Lansing Jr. and Robert Yates from New York and Luther Martin of Maryland, simply left the Convention, but even among those who stayed, three delegates (George Mason and Edmund Randolph of Virginia and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts of Massachusetts) decided not to sign.

Of these individuals, George Mason might have been the most important because, just a week before the Constitution was signed, Mason had proposed the addition of a bill of rights, which 10 of 10 states voting had rejected as unnecessary. One of the reasons that Mason had offered for adding such a bill was that “it would give great quiet to the people” (Farrand, 1966, II, 587).

When the Constitution was sent to the states for ratification, supporters of the document, arguably seeking to minimize the differences between the proposed constitution and its predecessor, called themselves Federalists. Capitalizing on the fact that they were offering solutions to what they perceived to be the problems under the Articles, they further dubbed those who opposed ratification as Anti-Federalists.

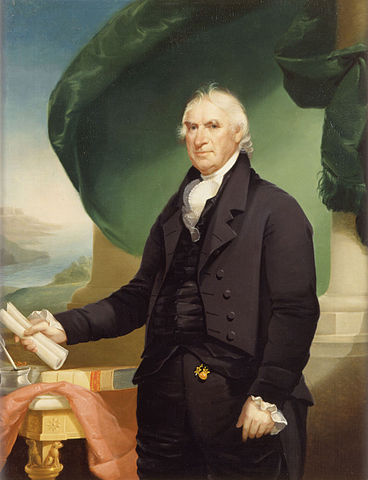

Patrick Henry was an outspoken anti-Federalist. The Anti-Federalists included small farmers and landowners, shopkeepers, and laborers. When it came to national politics, they favored strong state governments, a weak central government, the direct election of government officials, short term limits for officeholders, accountability by officeholders to popular majorities, and the strengthening of individual liberties. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain, portrait by George Bagby Matthews and Thomas Sully)

Anti-Federalists were concerned about excessive power of national government

The Anti-Federalists included small farmers and landowners, shopkeepers, and laborers. When it came to national politics, they favored strong state governments, a weak central government, the direct election of government officials, short term limits for officeholders, accountability by officeholders to popular majorities, and the strengthening of individual liberties. In terms of foreign affairs, they were pro-French.

Federalists were, as a whole, better organized and connected. Writing under the pen name of Publius, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay wrote a series of 85 powerful newspaper essays known as The Federalist Papers. To combat the Federalist campaign, the Anti-Federalists published a series of articles and delivered numerous speeches against ratification of the Constitution.

These independent writings and speeches have come to be known collectively as The Anti-Federalist Papers.

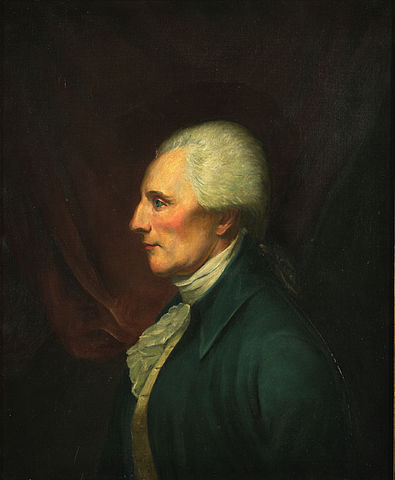

Although Patrick Henry, Melancton Smith, and others eventually came out publicly against the ratification of the Constitution, which they would vigorously debate in the state ratifying conventions, the majority of the Anti-Federalists advocated their position under pseudonyms. Nonetheless, historians have concluded that the major Anti-Federalist writers included Robert Yates (Brutus), most likely George Clinton (Cato), Samuel Bryan (Centinel), and either Melancton Smith or Richard Henry Lee (Federal Farmer).

By way of these speeches and articles, Anti-Federalists brought to light fears of:

- the excessive power of the national government at the expense of the state government;

- the disguised monarchic powers of the president;

- apprehensions about a federal court system and its control over the states;

- fears that Congress might seize too many powers under the necessary and proper clause and other open-ended provisions;

- concerns, partly based on the writing of the French philosopher, the Baron de Montesquieu and addressed in Federalist No. 10, that republican government could not work in a land the size of the United States;

- special concern over the role of the Senate in ratifying treaties without concurrence in the House of Representatives;

- fear that Congress was not large enough adequately to represent the people within the states;

- and their most successful argument against the adoption of the Constitution — the lack of a bill of rights to protect individual liberties.

George Clinton was most likely a writer of The Anti-Federalist Papers under the pseudonym Cato. These papers were a series of articles published to combat the Federalist campaign. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain, portrait by Ezra Ames)

Anti-Federalists pressured for adoption of Bill of Rights

The Anti-Federalists failed to prevent the adoption of the Constitution, but their efforts were not entirely in vain. Even before the adoption of the First Amendment, the debates and their outcome thus vindicated the importance of freedom of speech and press in achieving national consensus. Moreover, Anti-Federalists, most notably Patrick Henry, acceded to the Convention and sought legal means of change once the document had been ratified because they believed that it had been properly ratified.

Although many Federalists initially argued against the necessity of a bill of rights to ensure passage of the Constitution, they promised to add amendments to it specifically protecting individual liberties. Upon ratification, James Madison introduced 12 amendments during the First Congress in 1789. The states ratified 10 of these, which took effect in 1791 and are known today collectively as the Bill of Rights.

Had Anti-Federalists drafted the amendments, they would have undoubtedly contained structural reforms within the new government that Federalists successfully avoided in part by heading off pressures for a second constitutional convention that might have reversed many of the provisions of the first. Madison’s hope for an amendment in the Bill of Rights that would limit the states was not adopted, undoubtedly because of opposition by Anti-Federalists who already feared the power of the new national government.

Although the Federalists and Anti-Federalists reached a compromise that led to the adoption of the Constitution, this harmony did not filter into the presidency of George Washington.

Political division within the cabinet of the newly created government emerged in 1792 over fiscal policy. Those who supported Alexander Hamilton’s aggressive policies and expansive constitutional interpretations formed the Federalist Party, while those, including some former Federalists, who supported Thomas Jefferson’s view favoring stricter constitutional construction and opposing the establishment of a national bank, the assumption of state debts, and other Hamiltonian proposals formed the Jeffersonian Party.

The Jeffersonian party, led by Jefferson and James Madison, became known as the Republican or Democratic-Republican Party, the precursor to the modern Democratic Party.

Richard Henry was a possible writer of anti-Federalist essays with the pseudonym Federal Farmer. (Image via National Portrait Gallery, public domain, portrait by Charles Wilson Peale)

Election of Jefferson repudiated the Federalist-sponsored Alien and Sedition Acts

The Democratic-Republican Party gained national prominence through the election of Thomas Jefferson as president in 1801.

This election is considered a turning point in U.S. history because it led to the first era of party politics, pitting the Federalist Party against the Democratic-Republican Party. This election is also significant because it served to repudiate the Federalist-sponsored Alien and Sedition Acts — which made it more difficult for immigrants to become citizens and criminalized oral or written criticisms of the government and its officials — and it shed light on the importance of party coalitions.

In fact, the Democratic-Republican Party proved to be more dominant due to the effective alliance it forged between the Southern agrarians and Northern city dwellers.

The election of James Madison in 1808 and James Monroe in 1816 further reinforced the importance of the dominant coalitions within the Democratic-Republican Party.

With the death of Alexander Hamilton and retirement of John Quincy Adams from politics, the Federalist Party disintegrated.

After the War of 1812 ended, partisanship subsided across the nation. In the absence of the Federalist Party, the Democratic-Republican Party stood unchallenged. The so-called Era of Good Feelings followed this void in party politics, but it did not last long with the Federalist Party later being replaced respectively by the Whig and Republican Parties.

Some scholars see echoes of the Federalist/Anti-Federalist debates in the continuing tension between those who emphasize state over national powers, in proposals to reduce and limit terms in public office, and in disagreements between those who are more likely to embrace new institutional changes and those who are fearful that they might lead to unintended negative consequences..

This article was originally published in 2009. Mitzi Ramos is an instructor of political science at Northeastern Illinois University. John R. Vile is the dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University and a history professor.