William Francis “Frank” Murphy (1890–1949), who served on the Supreme Court from 1940 to 1949, wrote eloquently about the importance of First Amendment freedoms. Except in a few cases he championed individual freedoms and repeatedly voiced his belief that religious freedom was entitled to great constitutional protection.

Murphy was governor of Phillippines and Michigan

Murphy was born in Harbor Beach, Mich. He earned undergraduate and law degrees from the University of Michigan and was then in private practice for three years. After military service in Europe during World War I, he served in Detroit as an assistant U.S. attorney, as a judge on a criminal court, and as mayor of the city.

He supported Franklin D. Roosevelt’s bid for the presidency in 1932 and was rewarded with the governorship of the Philippines. Murphy was elected governor of Michigan in 1936 but was defeated for reelection two years later. Roosevelt then named him U.S. attorney general. One year later Roosevelt nominated him to the Supreme Court, and the Senate unanimously confirmed him in 1940.

Murphy wrote several majority opinions in First Amendment decisions

Murphy wrote several majority opinions for the Court in First Amendment decisions. He wrote the Court’s opinion in Thornhill v. Alabama (1940), finding that labor picketing was entitled to First Amendment protection: “Free discussion concerning the conditions in industry and the causes of labor disputes appears to us indispensable to the effective and intelligent use of the processes of popular government to shape the destiny of modern industrial society.”

He also wrote Hartzel v. United States (1944), in which the Court reversed the conviction of an anti-war dissenter for violating the Espionage Act of 1917.

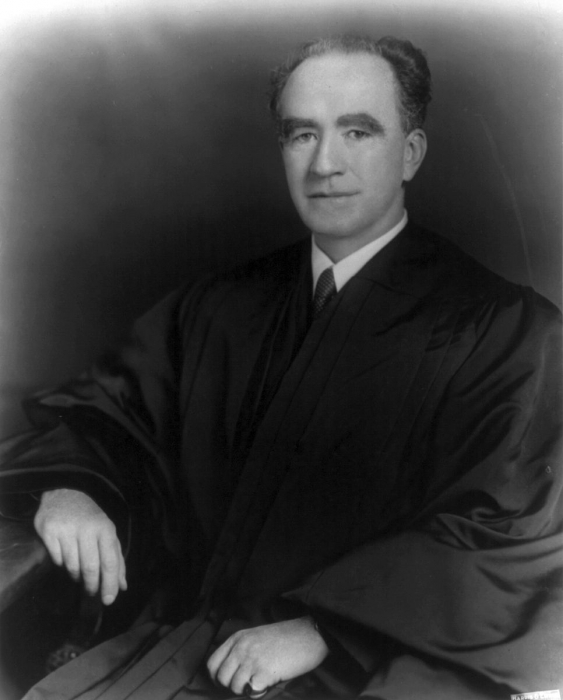

Francis Murphy during his time as U.S. attorney general in 1940. As a Supreme Court justice, Murphy wrote several majority opinions for the Court in First Amendment decisions, including in picketing and espionage. (Public domain)

Murphy strongly backed ‘spiritual freedom’

Murphy often ruled in favor of Jehovah’s Witnesses in cases involving freedom of religion, thus earning the respect of Hayden C. Covington, an attorney who represented the Witnesses.

In his dissent in Jones v. City of Opelika (1942), Murphy — noting the “unpopularity” of Jehovah’s Witnesses and the difficulties they had faced — observed that there was “an arresting parallel” between their troubles “and the struggles of various dissident groups in the American colonies for religious liberty which culminated in the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, and the First Amendment.”

In his concurring opinion in Martin v. City of Struthers (1943), he wrote, “I believe that nothing enjoys a higher estate in our society than the right given by the First and Fourteenth Amendments freely to practice and proclaim one’s religious convictions.” He dissented in the Court’s decision in Prince v. Massachusetts (1944), in which the majority convicted a woman who was a Jehovah’s Witness for allowing children to sell religious magazines on the street. Murphy wrote, “Religious freedom is too sacred a right to be restricted or prohibited in any degree without convincing proof that a legitimate interest of the state is in grave danger.”

Along with Justices William O. Douglas and Hugo L. Black, Murphy changed his mind about compulsory flag-salute laws in public schools. Murphy had voted to uphold such a Pennsylvania law, which was applied against Jehovah’s Witnesses in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), but he voted with the new majority to invalidate a similar West Virginia law in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). Murphy explained, “Reflection has convinced me that as a judge I have no loftier duty or responsibility than to uphold that spiritual freedom to its farthest reaches.”

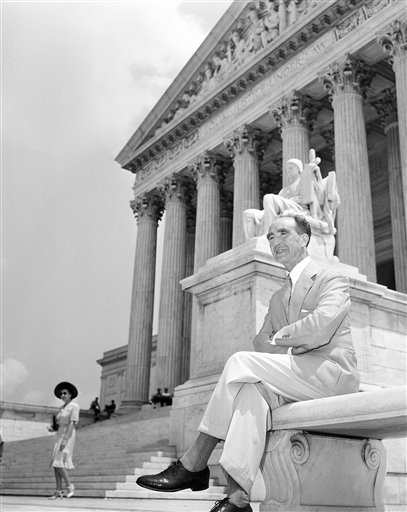

Justice Frank Murphy sits on a bench outside the U.S. Supreme Court in 1942. Murphy was known for his eloquent First Amendment opinions. In Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942), he established that there are certain categories of speech that are not protected by the First Amendment. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

Murphy described limits to freedom of speech

Despite his generally broad protection for First Amendment freedoms, Murphy was the author of the Court’s opinion in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942), in which he wrote a passage that courts frequently cite when they stress that the First Amendment does not protect all forms of speech: “There are certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which has never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem. These include the lewd and obscene, the profane, the libelous, and the insulting or ‘fighting’ words — those which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.”

Murphy’s fighting-words exception establishes the categorical exclusion model of First Amendment jurisprudence — that one way to distinguish protected from unprotected expression is to determine whether speech falls into certain categories, such as fighting words, obscenity, or child pornography.

Black’s dissenting opinion in Cohen v. California (1971) neatly captures both Murphy’s broad protection of the First Amendment and his creation of the fighting-words doctrine. Although a narrow majority of the Court ruled that the profane message “Fuck the Draft,” displayed on a jacket worn by Paul Robert Cohen in a courthouse, was protected expression, Justice Black contended that the message was a form of fighting words. Black wrote that Cohen “appears to be well within the sphere of Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, where Mr. Justice Murphy, a known champion of First Amendment freedoms, wrote for a unanimous bench.”

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.