Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), printer, inventor, scientist, and statesman, occupies a distinguished place in U.S. history. He not only played an influential role in the Revolutionary War era and the fight for American independence, but also helped to shape the U.S. Constitution and vision for the new nation. Even before there was a First Amendment, he was a lifetime champion of the freedoms it embodied, particularly freedom of the press.

Franklin became a printer and publisher of a newspaper

Franklin was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to Josiah Franklin and Abiah Folger. He attended Boston Latin School, but did not graduate. His keen intellect grew through his intensive studying and reading. Franklin was apprenticed at an early age to his older brother James, who published the first independent newspaper in the Colonies, the New England Courant.

His apprenticeship ended abruptly at the age of 17 when he moved to Philadelphia. Franklin’s knowledge of the printing business grew, and he bought and became the publisher of the Pennsylvania Gazette. He used the newspaper as a forum for political discourse in the city. He also published Poor Richard’s Almanack, which was widely distributed and known for its witty aphorisms.

Franklin had diverse professional interests

Franklin’s professional interests were diverse. In 1731 he was one of several young men who began the first public library, located in Philadelphia. A prolific writer, he became known for Poor Richard’s Almanack (1733) and Father Abraham’s Sermon (1758). In 1743 he founded the American Philosophical Society.

The source of many inventions, Franklin was best known for his famous kite-flying experiment that he conducted during a lightning storm, and he wrote a scholarly paper on electricity. In the early 1740s, he developed a vision for the Academy and College of Philadelphia, which opened in 1755 and later merged with the University of the State of Pennsylvania to become the University of Pennsylvania.

Franklin was involved in the early American struggle

Franklin became involved in politics in the 1740s and 1750s and was an advocate of an early plan of colonial association known as the Albany Plan of Union. In addition to numerous political appointments, Franklin displayed his diplomatic brilliance when he was sent to Europe to advance colonial relations with Great Britain and France. After a five-year stay in London, he returned to the Colonies in 1762 and developed a proposal for managing colonial relations with the Indians. The Colonies then sent him back to Great Britain to protest the contentious Stamp Act of 1765 and Townshend Act of 1767.

After Franklin, who had been serving as a deputy postmaster, took responsibility for leaking incriminating correspondence between Governor Thomas Hutchinson and Andrew Oliver, the governor and lieutenant governors of Massachusetts, he was humiliated in an appearance before the British Parliament and soon departed for America.

The Declaration of Independence, signed on July 4, 1776, was written primarily by Virginian Thomas Jefferson, with assistance from both Franklin and John Adams. Franklin helped console Jefferson during the contentious debates in the Continental Congress that altered Jefferson’s draft. After being appointed to a committee to design a seal for the new nation, Franklin proposed one with a scene depicting Moses and the children of Israel escaping Egypt as Pharaoh and his army were drowned in the sea.

Later, in the fight for American independence, Franklin, who made a particularly good impression on the French people, was instrumental in securing financial aid and military backing from the French king to help defeat the British. Franklin’s support for the American cause estranged him from his son, who had been governor of New Jersey.

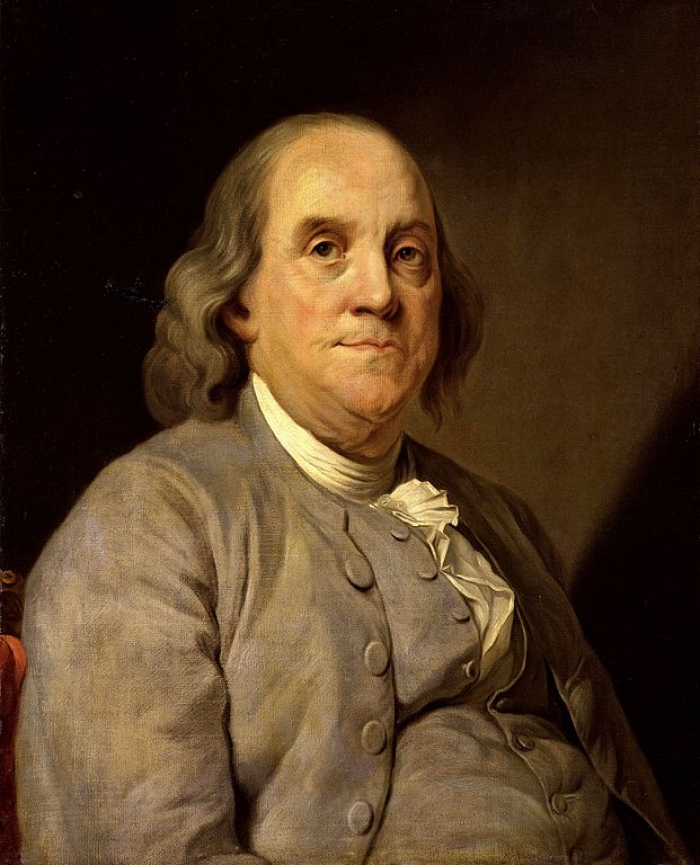

Benjamin Franklin viewed the flow of ideas through freedom of expression as essential to democracy, and he practiced these rights through numerous literary endeavors and ownership of the Pennsylvania Gazette. Franklin viewed free expression as the principal antagonist of tyrannical regimes. He also defended religious toleration and freedom. He vested authority in the actions of man rather than in an absolute religious doctrine. (Image via National Portrait Gallery, after Joseph Siffred Duplessis, based on a work of 1783, public domain)

After Lord Cornwallis surrendered on behalf of the British army at Yorktown on October 17, 1781, Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay were sent to Europe to negotiate on behalf of the new nation. Franklin succeeded in pacifying all parties enough to sign the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which formally recognized America’s new status.

At the age of 81, Franklin was the oldest delegate to attend the Constitutional Convention of 1787. His was a conciliatory voice that was at least in part responsible for hammering out the landmark “Great Compromise,” which solidified elements of both the Virginia and New Jersey Plans by granting representation on the basis of population (sought by the large states) in the House of Representation and equal representation (advocated by the small states) in the Senate.

At the height of controversies over state representation, Franklin had unsuccessfully proposed that the delegates should begin each day at prayer.

At the end of the Convention, Franklin was more successful in delivering an influential speech, urging delegates to accept the document as the best that a collective body was likely able to craft. As delegates signed the Constitution, Franklin further optimistically professed to believe that the sun painted on the back of the chair on which George Washington, who had presided over the Convention had been sitting, was a rising rather than a setting sun.

Franklin championed press freedom

Franklin’s reputation as a champion of U.S. independence and as a statesman is paralleled only by that of George Washington. In addition to championing freedom of the press (Franklin was the first to publish Cato’s “Essay on Free Speech” in 1722 after his brother was imprisoned for criticizing the Massachusetts government), Franklin vigorously supported the rights of religious freedom, speech, and assembly that were ultimately incorporated into the First Amendment.

Franklin viewed the flow of ideas through freedom of expression as essential to democracy, and he practiced these rights through numerous literary endeavors and ownership of the Pennsylvania Gazette. Franklin viewed free expression as the principal antagonist of tyrannical regimes. He also defended religious toleration and freedom. He vested authority in the actions of man rather than in an absolute religious doctrine.

Franklin was a particularly gifted satirist and often wrote anonymously or under a pseudonym. As a teenager, he wrote humorous essays under the name of Silence Dogood, who was portrayed as a middle-aged widow. Especially when he served abroad, such anonymous speech gave him the opportunity to gauge public opinion on matters about which he had written without being prejudiced by his American authorship.

In November of 1737, Franklin printed (and possibly authored) an essay in The Pennsylvania Gazette entitled “On Freedom of Speech and the Press,” which observed that “Freedom of speech is a principal pillar of a free government.” It further observed that “An evil magistrate intrusted with power to punish for words, would be armed with a weapon the most destructive and terrible. Under pretence of pruning off the exuberant branches, he would be apt to destroy the tree” (Shibley 2016)

Franklin eventually became a proponent of freeing American slaves. He was the oldest signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, bringing not only seasoned intellect to the creation of these documents, but also insight and patriotism.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in January 2024 by John R. Vile, a professor of history and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. Daniel Baracskay teaches in the public administration program at Valdosta State University.