The First Amendment proved to be a crucial tool for the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, as ministers preached, protesters marched, organizations litigated, advocates petitioned, and the press reported on racial discrimination.

Calls by African Americans and others for broad societal change culminated in historic pieces of federal legislation that paved the way for greater equality in American society, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

The expressive actions of protesters and activists also led to the considerable growth of First Amendment precedent. The movement witnessed such an expansion of free expression principles through First Amendment cases that scholar Harry Kalven Jr. wrote, “We may come to see the Negro as winning back for us the freedoms the Communists seemed to have lost for us” (1965: 6).

Court established right of freedom of association

The Supreme Court ruled in NAACP v. Alabama (1958) that Alabama could not force the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to disclose its membership list. The Court established the First Amendment right of freedom of association, noting that “freedom to engage in association for the advancement of beliefs and ideas is an inseparable aspect of the ‘liberty’ assured by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which embraces freedom of speech.”

The Court accepted similar limitations on a Florida state legislative investigation of the NAACP in Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Committee (1963).

In NAACP v. Button (1963), the Court further established the right of an organization to litigate, signaling the birth of the public interest law firm. The Court ruled that the NAACP had the right to refer individuals who wanted to sue in public school desegregation cases to lawyers and to pay their litigation expenses.

A Virginia law had forbidden any organization from compensating an attorney in a case in which it had no direct monetary interest. Virginia officials charged the NAACP with violating these rules by encouraging people to become plaintiffs in desegregation cases, referring them to private attorneys, and then paying their litigation expenses. The Court wrote, however, that the NAACP’s actions were “modes of expression and association protected by the First Amendment.”

Free press fortified with higher standards on proving libel

The Court’s landmark decision nationalizing libel law in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964) is arguably the most important First Amendment precedent arising during the Civil Rights Movement.

In that ruling, the Court held that state libel laws must comport with overarching First Amendment principles to ensure that “debate on public issues should be robust, uninhibited and wide-open.” The justices held that public officials could not recover damages for libel unless they could show actual malice — defined as knowing falsity or reckless disregard for the truth — by clear and convincing evidence.

This high standard freed the press to report on various civil rights abuses. For this reason, Anthony Lewis (1991) argues that the Court’s decision in Sullivan not only changed libel law, but also saved the Civil Rights Movement.

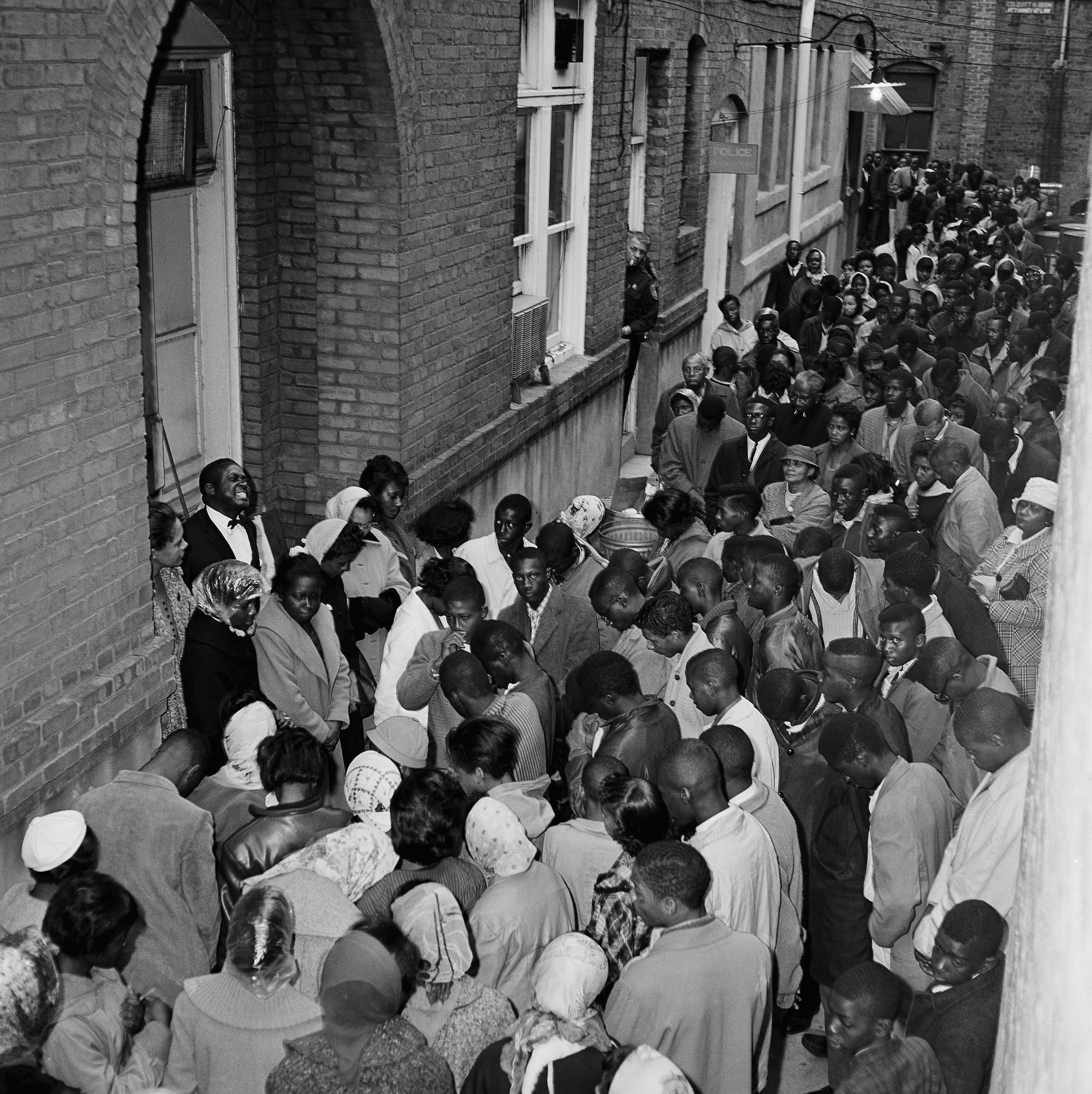

The Civil Rights Movement led to court precedents in the areas of protests and sit-ins. In Garner v. Louisiana (1961), the Court overturned the disturbing-the-peace convictions of five African-Americans who had engaged in sit-ins at an all-white restaurant counter in Baton Rouge. In this photo, members of the Congress of Racial Equality (C.O.R.E.), in a sit-in at the Hotel Muehlebach barber shop occupy all chairs on July 2, 1964 in Kansas City. Just after President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Bill in Washington, a C.O.R.E. member asked for, and was refused, service. Immediately a sit-in began with marching, singing and clapping of hands. With the announcement that the barber shop was closed, the marchers and sitters said they’d be back when the shop opens in the morning. (AP Photo/WPS, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Civil Rights Movement strengthened assembly and petition rights

The Court established another important First Amendment precedent in Edwards v. South Carolina (1963), in which it struck down the breach-of-the-peace convictions of 187 African American students who had marched to the South Carolina statehouse, protesting segregation and carrying signs with such messages as “Down with Segregation.”

The Court reasoned that the arrests violated the students’ freedom of assembly and petition rights, noting that the students’ expressive actions “reflect an exercise of these basic constitutional rights in their most pristine and classic form.”

The Court added that the government could not criminalize “the peaceful expression of unpopular views.” It also allowed protesters to publicly oppose segregation by striking down licensing laws allowing city officials to deny permits for demonstrations on a selective and discriminatory manner.

For example, in Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham (1969), the Court reiterated that licensing laws violate the First Amendment if they grant unbridled discretion to city officials and provide no guiding standards.

In Garner v. Louisiana (1961), the Court overturned the disturbing-the-peace convictions of five African-Americans who had engaged in sit-ins at an all-white restaurant counter in Baton Rouge.

In a concurring opinion, Justice John Marshall Harlan II wrote that a sit-in “is as much a part of the free trade of ideas as is verbal expression.” In Brown v. Louisiana (1966), the Court relied similarly on the First and Fourteenth Amendment rights of freedom of speech, assembly, and petition to invalidate the convictions of several protesters who had engaged in a sit-in at a public library.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.