In United States v. Congress of Industrial Organizations, 335 U.S. 106 (1948), the Supreme Court upheld a federal district court’s dismissal of an indictment under the Corrupt Practices Act of 1925 as amended by the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947. In so doing, it decided that the publication of “The CIO News,” a weekly periodical that had endorsed a judicial candidate, did not violate the statute because the statute was not intended to interfere with First Amendment rights.

CIO said new labor law violated First Amendment rights

The CIO and its president, Philip Murray, had moved to dismiss the indictment against them on the basis that the amended law violated their rights of speech, press, and assembly. The district court had agreed to dismiss on the basis that the law was not intended to prohibit publication of a periodical simply because it endorsed a judicial candidate, and the government had appealed directly to the Supreme Court.

Court found law not meant to prohibit distribution of periodicals to union members

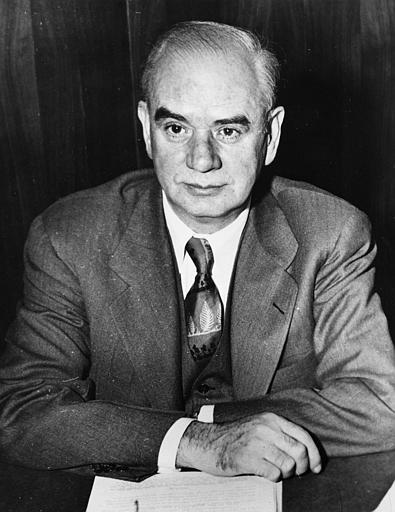

Justice Stanley F. Reed wrote the decision for four justices, deciding that the indictment did not charge an offense under the law. Reviewing the history of the legislation at issue, Reed did not think that a “contribution or expenditure” connected to elections was designed to prohibit the distribution of periodicals, like the one here. He observed that the periodical had been funded by dues from its members and was only distributed to them.

In a concurring opinion, Justice Felix Frankfurter stressed the need to avoid litigation in cases that did not involve real controversies but agreed that the Court should so construe laws as to avoid constitutional issues.

Justice Rutledge said law imposed on First Amendment freedoms

In another concurrence, Justice Wiley B. Rutledge argued that the Court had misconstrued the statute and that it was “patently invalid as applied in these circumstances.” Rutledge felt that statutes imposing on First Amendment freedoms were not entitled to the same deference as others. In this case, Rutledge did not believe that the law had been “narrowly drawn to meet the precise evil the legislature seeks to curb.”

The law at issue had crossed the line from “regulation” to “prohibition.” Consistent with later rulings, Rutledge thought there were ways to allow dissenting union members to make their views known or to be exempted from contributing to the cost of views they opposed without prohibiting union expression altogether.

He observed, “It would be a very great infringement of individual as well as group freedoms, affecting vast numbers of our citizens, if labor unions could be deprived of all right of expression upon pending political matters affecting their interests.”

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.