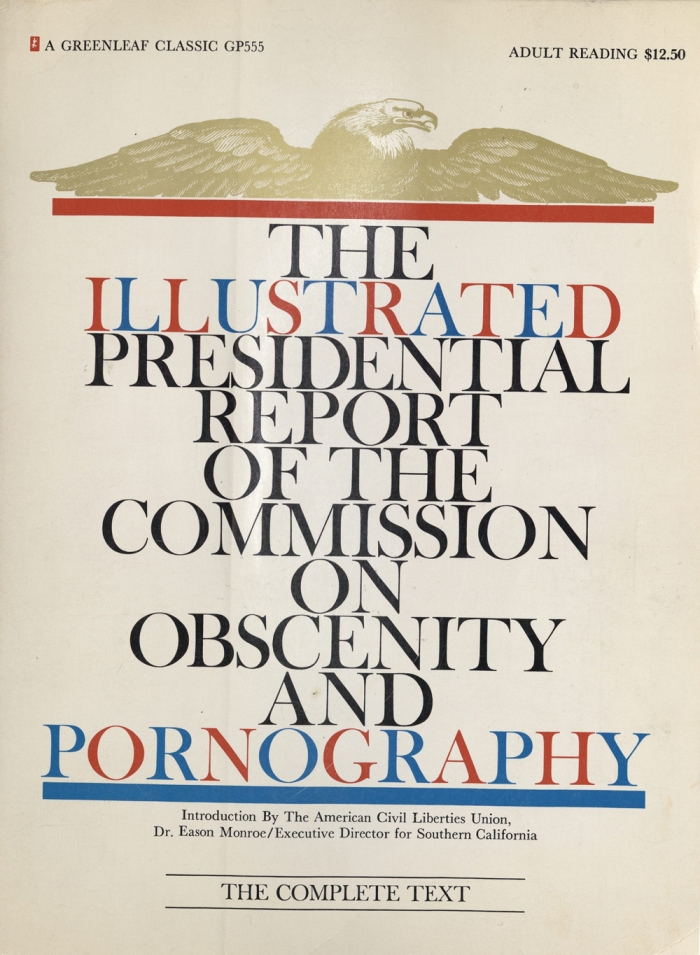

In Hamling v. United States, 418 U.S. 87 (1974), the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of several individuals, including William L. Hamling, for their role in distributing advertisements of the book The Illustrated Presidential Report of the Commission on Obscenity and Pornography. The decision afforded defendants less leeway to challenge convictions based on jury instructions regarding community standards and allowed convictions for obscenity under the First Amendment, provided defendants know the general content and character of the material.

Hamling convicted for mailing obscenity

Hamling and others had mailed brochures advertising the book with depictions of individuals engaged in a variety of sexual acts including masturbation and various forms of sodomy. A jury had found the pictures to be obscene.

A federal district court found the defendants guilty on 12 counts in December 1971, and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed in June 1973. The Court of Appeals reviewed the convictions after the Supreme Court’s intervening decision in Miller v. California (1973) and again affirmed the convictions.

Court said new obscenity standard was easier to use

On appeal, the Supreme Court affirmed by a narrow 5-4 vote. Writing for the majority, Justice William H. Rehnquist rejected the defendants’ arguments that their convictions should be invalidated because they were convicted under obscenity standards issued before the Miller obscenity decision. Instead, the defendants were convicted under the older standard articulated in Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966). However, Rehnquist pointed out that the Miller standard actually made it easier for prosecutors to establish obscenity than the previous Memoirs test.

Geographical obscenity standards considered in convictions

Rehnquist also rejected the defendants’ arguments that they could not be convicted unless the prosecution introduced expert testimony as to the obscenity of the advertisement in question. They argued that their convictions should be set aside because the trial judge instructed the jury that they could judge the advertisement under a national standard of obscenity, a concept that the Court rejected in Miller in favor of local standards. Rehnquist wrote that the Court’s holding in Miller that “California could constitutionally proscribe obscenity in terms of a ‘statewide’ standard did not mean that any such precise geographic area is required as a matter of constitutional law.” He reasoned that the jury instructions with reference to “the nation as a whole” did not materially prejudice the defendants in this case.

The defendants also argued that they could not be convicted unless the prosecution showed that they knew the material in question was legally obscene. Rehnquist noted that it was “constitutionally sufficient that the defendant knew about the contents . . . the character and nature of the materials” he distributed. Rehnquist wrote, “To require proof of a defendant’s knowledge of the legal status of the materials would permit the defendant to avoid prosecution by simply claiming that he had not brushed up on the law.”

Dissenters said conviction violated the First Amendment

Justice William O. Douglas dissented, pointing out that the advertisement in question only provided visual summaries of the content of the national presidential report on obscenity. “If officials may constitutionally report on obscenity, I see nothing in the First Amendment that allows us to bar the use of a glossary factually to illustrate what the report discusses,” he wrote.

Also dissenting were Justices William J. Brennan Jr., Potter Stewart, and Thurgood Marshall. Brennan reiterated his dissenting view in Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton (1973) that obscenity laws by their nature were too vague to satisfy constitutional standards. He argued that the defendants’ due process rights were violated by the trial judge’s refusal to allow them to offer evidence of local community standards: “To affirm their convictions without affording them opportunity to try the case on the ‘local’ standards basis is a clear denial of due process.”

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.