In Police Department of Chicago v. Mosley, 408 U.S. 92 (1972), the Supreme Court held that the government could not selectively exclude speakers from the public sphere based on the content of their message. The case turned on the intersection of the freedom of speech clause of the First Amendment and the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Chicago ordinance prevented picketing near schools

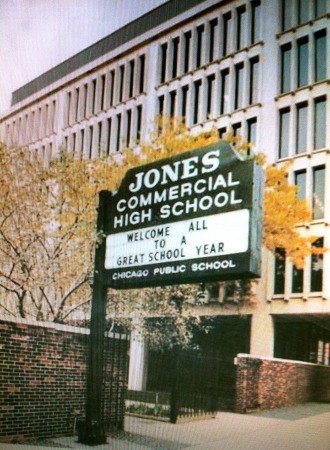

The law in question was an ordinance passed by the city of Chicago preventing all picketing within 150 feet of a school, except for peaceful picketing of any school involved in a labor dispute. Earl Mosley, a federal postal employee, had been picketing Jones Commercial High School by walking along the sidewalk holding up a sign charging the school with “black discrimination.” When Mosley heard about the ordinance, he called the police department to ask how it would affect him and was informed that his picketing must stop or he would be arrested.

Mosley filed a complaint, alleging that the ordinance denied him his right to free speech and to equal protection under the laws. The District Court dismissed Mosley’s complaint, but the Seventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed, holding that the ordinance was overbroad because it prevented even peaceful picketing. The Supreme Court affirmed this ruling but found the ordinance unconstitutional on different grounds.

Supreme Court found ordinance unconstitutional

The entire court agreed on the result, although only seven justices joined the majority opinion, written by Justice Thurgood Marshall. He held that the ordinance was unconstitutional because it created a content-based regulation of speech that was not justified by any substantial government interest. Marshall observed that picketing is expressive conduct and thus protected by the First Amendment and that the Chicago ordinance treated two classes of speakers (labor and nonlabor picketers) differently, giving rise to a denial of equal protection. Marshall pointed out that not only did the ordinance distinguish between classes of speakers, but it did so on the basis of the content of the speakers’ messages, which is constitutionally impermissible in the absence of a substantial government interest linked to the content.

Justice Marshall said content-based regulations must be narrowly tailored

In oft-cited language, Marshall wrote: “But, above all else, the First Amendment means that government has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content.” Thus, content-based regulations are inherently constitutionally suspect and must be narrowly tailored to a substantial government interest. Marshall argued that no such interest was served by the distinction between labor and nonlabor picketing. He also pointed out that the government had other options for regulating picketing. Although content-based regulations necessitate a substantial government interest, he said, regulations of “time, place and manner” require only a significant government interest, a less stringent standard of review.

Justices Harry A. Blackmun and William H. Rehnquist concurred in the result. Chief Justice Warren E. Burger joined the majority opinion but wrote a short, separate concurrence.

Harvey Barnett, the Chicago-based lawyer who represented Earl Mosley, reflected on the historic case in a 2015 interview. “What Mr. Mosley did was quintessentially American,” Barnett reflects. “He was a solitary figure who stood up for what he believed in – and he was right. It still gives me chills.”

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2017. Katrina Hoch was a doctoral student at the University of California San Diego.