In Pell v. Procunier, 417 U.S. 817 (1974), the Supreme Court upheld California prison restrictions on face-to-face interviews with inmates. Inmates and journalists had challenged the restrictions as a violation of the First Amendment right of freedom of the press.

Three journalists — Eve Pell, Betty Segal, and Paul Jacobs — and four inmates — Booker T. Hillery Jr., John Larry Spain, Bobby Bly, and Michael Shane Guile — challenged the constitutionality of a California Department of Corrections policy that banned press interviews of inmates. The suits were filed separately.

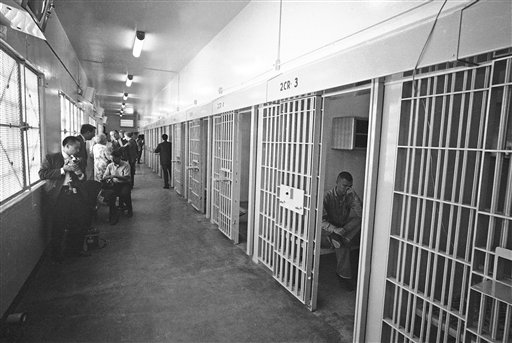

The policy provided that “[p]ress and other media interviews with specific individual inmates will not be permitted.” A federal district court ruled in favor of the inmates but not the journalists. The California Department of Corrections and the journalists both appealed the district court rulings to the Supreme Court.

Court rejects press freedom argument, upholds California ban on prisoner interviews

The Court rejected the claims of both inmates and journalists in a majority opinion written by Justice Potter Stewart.

He observed that the corrections system had at least three functions — crime deterrence, the quarantining of criminal defendants from society, and the internal security of the prisons.

Although California had limited face-to-face interviews with the press, it left other methods of communications open. These included communication by mail, previously addressed in Procunier v. Martinez (1974); communications through visitations from family and friends; and communications of these individuals with the media.

Stewart noted that “the entry of people into prisons for face-to-face communications with inmates” created “security and related administrative problems,” noting that the current policy had been implemented after an earlier policy permitting the media to select individual inmates for interviews had created special problems that had led to prison violence.

This experience, along with the Court’s opinion in Branzburg v. Hayes (1972), limiting the confidentiality of reporters’ sources from grand jury inquiry, further undermined the claim of reporters to special access under freedom of the press. Stewart argued that the government had no “affirmative duty to make available to journalists sources of information not available to members of the public generally.”

Other justices thought California’s rule was overly broad

In a partial concurrence, Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. agreed that inmates had no personal constitutional right as individuals to talk to reporters but argued that the absolute ban on such interviews impermissibly interfered with freedom of the press.

Justice William O. Douglas’s dissenting opinion, joined by Justices William J. Brennan Jr. and Thurgood Marshall, contended that the prison regulations were overly broad as applied to inmates and that the Court’s decision respecting the rights of reporters did not take sufficient account of “the public’s right to know.” Although he favored reasonable “time, place, and manner” restrictions, Douglas thought the prison’s absolute ban on such press access was also overly broad.