In deciding Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co., 497 U.S. 1 (1990), the Supreme Court ruled that opinions can be defamatory and that no broad constitutional shield for the expression of defamatory opinions is appropriate. It was the first time the Court addressed whether libel laws were applicable to expressions of opinion.

Defamatory opinions were presumed to have First Amendment protection

The debate over constitutional protection for statements of opinion began long before the Supreme Court’s decision in Milkovich. Opinions were presumed to be protected, in part because U.S. common law was constructed in response to persecutions in England of those who dared criticize royalty.

The Court had also overturned libel verdicts against publications accusing plaintiffs of being “traitors” and involved in “blackmail.”

Most recently, in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974), the Court had suggested in dicta that “[u]nder the First Amendment there is no such thing as a false idea. However pernicious an opinion may seem, we depend for its correction not on the conscience of judges and juries but on the competition of other ideas.”

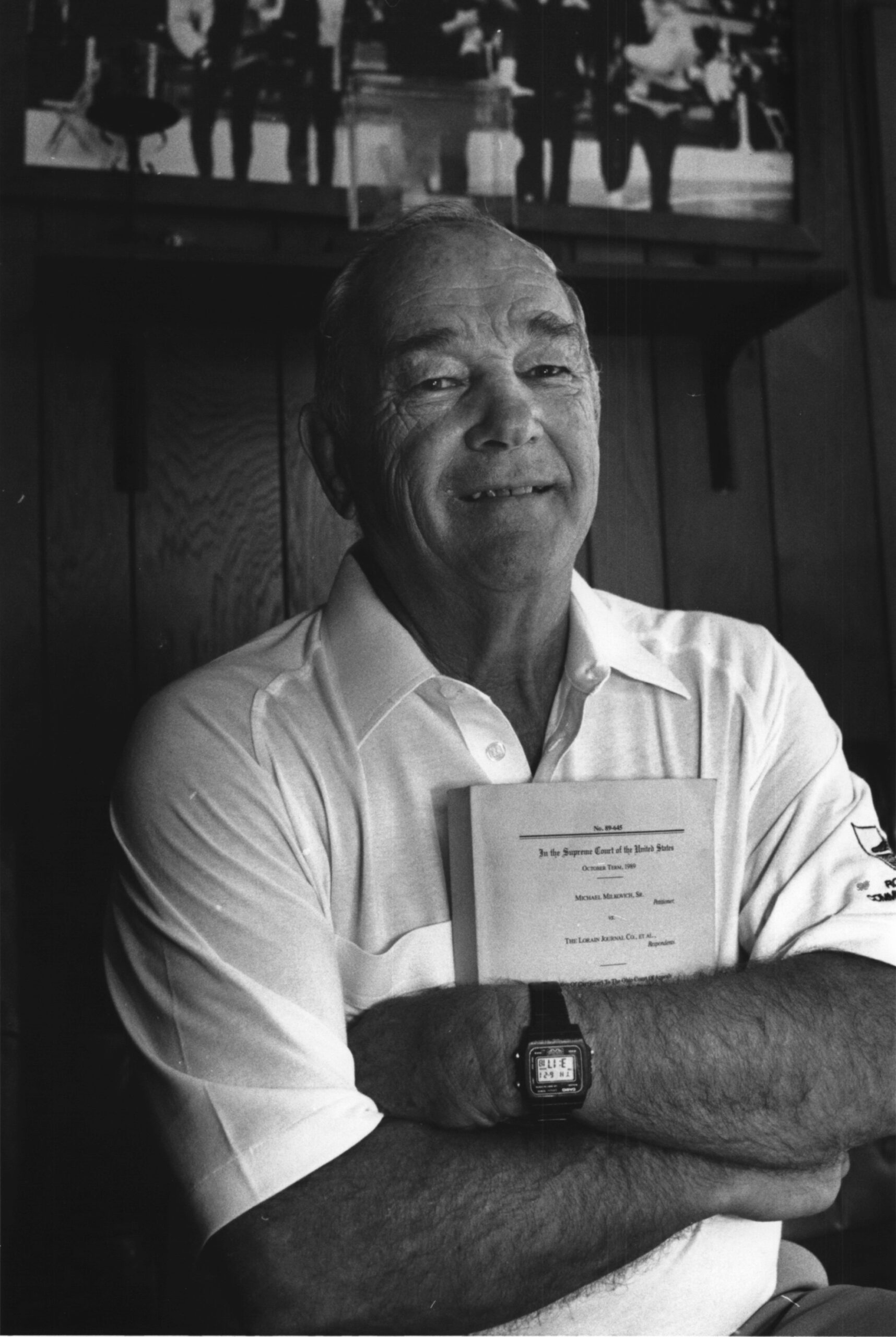

Milkovich sued after opinion column accused him of lying

Nevertheless, the Court addressed the issue straightforwardly when Michael Milkovich, an Ohio high school wrestling coach, sued for the damages he incurred when a newspaper opinion column asserted that he had lied under oath at a public hearing. Coach Milkovich charged in his suit that the newspaper had accused him of perjury. However, the trial judge granted the newspaper’s motion for summary judgment on the ground that the assertion in the newspaper column was opinion, and it therefore was constitutionally protected.

Court declined to recognize opinion as protected by First Amendment

In a 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court reversed “the Ohio courts’ recognition of a constitutionally required ‘opinion’ exception to the application of its defamation laws.”

Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist wrote the majority opinion, which reached its conclusion on the basis of three claims.

- First, the media were already protected by requirements that plaintiffs prove both fault and falsity; an additional requirement of a constitutional immunity for media opinions was not necessary.

- Second, because “expressions of ‘opinion’ may often imply an assertion of objective fact,” they may inflict “as much damage to reputation” as factual claims.

- And, third, opinions such as those expressed in the case at hand were “sufficiently factual to be susceptible of being proved true or false.” Courts should undertake this inquiry because of the social values at stake in the protection of individual reputations.

Milkovich, Masson restrained excesses of media analysts, investigators

Milkovich is one of two relatively recent Supreme Court decisions widely interpreted as designed to restrain the potential excesses of media analysts and investigators.

In Masson v. New Yorker Magazine (1991), the Court rejected constitutional protection for fabricated direct quotations, even when the purported direct statement was a “rational interpretation” of what was actually said. The Court held that attribution of fabricated quotations could satisfy the actual malice standard for libel involving public figures when “the alteration resulted in a material change in the meaning conveyed by the statement.”

Concerns arose about Milkovich’s impact on free speech

The Court’s decision in Milkovich has led to considerable apprehension among journalists who report on the alleged unethical behavior of public officials, professionals (such as art critics) whose judgments might be interpreted as product disparagement, and employers who write negative job appraisals, among others.

Some have assessed, however, that Milkovich has had less effect on defamation law than at first expected.

“After all, the Court’s recognition of protection for ‘imaginative expression,’ ‘loose, figurative’ language, and ‘rhetorical hyperbole‘ offered an alternative strategy to defendants in defamation cases. In response to Milkovich, media lawyers resorted to the simple expedient of substituting ‘rhetorical hyperbole’ for ‘opinion’ in their briefs. And most courts that later considered such cases applied the same standard they had previously applied and ‘reached the result that they likely would have before the Supreme Court decided [Milkovich],” writes Len Niehoff and Ashley Messenger in 2016 in “Milkovich v. Lorain Journal, Twenty-Five Years Later: The Slow, Quiet, and Troubled Demise of Liar Libel.”

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2018. Richard A. “Tony” Parker is an Emeritus Professor of Speech Communication at Northern Arizona University. He is the editor of Speech on Trial: Communication Perspectives On Landmark Supreme Court Decisions which received the Franklyn S. Haiman Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Freedom of Expression from the National Communication Association in 1994.