In United Mine Workers of America, District 12 v. Illinois State Bar Association, 389 U.S. 217 (1967), the Supreme Court found that the trial court’s decree preventing the United Mine Workers of America from hiring attorneys on a salaried basis to represent consenting union members in prosecuting workmen’s compensation claims before the Illinois Industrial Commission violated the freedom of speech, assembly, and petition provisions of the First Amendment.

The trial court’s decision had been affirmed by the state supreme court.

Supreme Court overturned ruling preventing union from hiring lawyer to represent members

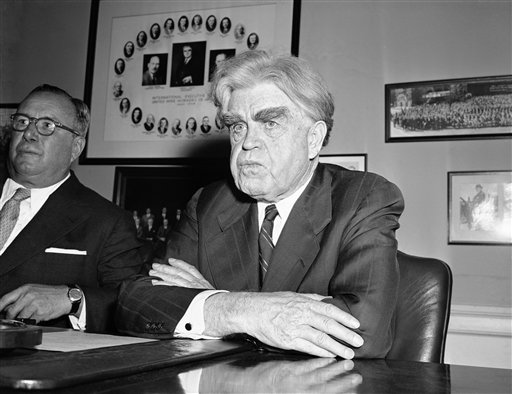

In his opinion for the Court, Justice Hugo L. Black relied chiefly on the precedents in Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia ex rel. Virginia State Bar (1964) and NAACP v. Button (1963). He noted that Illinois unions had hired attorneys for this purpose almost since enactment of the Illinois Workmen’s Compensation Act.

He then held that “the rights to assemble peaceably and to petition for a redress of grievances are among the most precious of the liberties safeguarded by the Bill of Rights” and were intimately connected with other First Amendment rights.

Restraints of such liberties could not be justified “merely because they were enacted for the purpose of dealing with some evil within the State’s legislative competence, or even because the laws do in fact provide a helpful means of dealing with such an evil.”

Court said First Amendment rights were impaired by state court’s decision

The First Amendment “does not protect speech and assembly only to the extent it can be characterized as political.” The state supreme court decree at issue “substantially impairs the associational rights of the Mine Workers and is not needed to protect the State’s interest in high standards of legal ethics.”

Justice Potter Stewart wrote a one-sentence concurrence. Justice John Marshall Harlan II dissented chiefly on federalism grounds, arguing that the union practice violated state bar canons preventing “the unauthorized practice of law by any lay agency.” Harlan opined that the litigation was closer in spirit to conduct than to speech and that “the States may reasonably regulate conduct even though it is related to expression.”

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.