Although Congress crafted and proposed the First Amendment and sometimes adopts legislation to enhance it, representatives and senators over time have also restricted each of the rights that the amendment protects.

First Amendment references Congress

The First Amendment specifically references Congress:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

But with the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court has also applied the First Amendment’s provisions to the states.

Congress has passed some laws interfering with religious freedom

The Court has further interpreted the establishment clause not only to prohibit government from creating a national religion, but also from showing preference for one religion over another, or promoting religious views over nonreligious ones. Regardless, Congress has toyed throughout much of its history with adopting a so-called Christian amendment to recognize God or Jesus within the Constitution but has yet to do so.

During the Civil War, however, it passed legislation to put the words “In God We Trust” on U.S. currency and in 1954 to add the words “Under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag. If the Supreme Court were to rule that “Under God” could not be recited in the pledge in public schools, Congress has the authority to propose an amendment — subject to ratification by three-fourths of the states — to reverse the decision, although similar proposals, to permit public prayer or devotional Bible reading in public schools, have consistently failed.

In Sherbert v. Verner (1963), the Warren Court established a test requiring a compelling interest by the government before infringing on free exercise rights. Later courts, however, retreated from this standard, allowing more latitude for congressional interference with religion.

The Court’s decision in Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990) essentially eliminated the Sherbert test. But Congress resurrected much of its substance by passing the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, which aimed to prevent laws substantially burdening individuals’ free exercise of religion.

The Court in turn limited the RFRA’s impact by restricting its application to federal laws only in City of Boerne v. Flores (1997). Congress responded, again, by passing the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000.

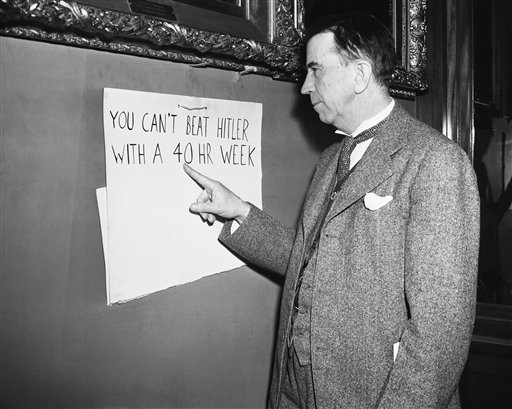

Although the Court generally made the ultimate decision on the constitutionality of congressional legislation, it often deferred to congressional judgments as to which speech constituted a danger. Thus in enacting the Smith Act of 1940, Congress made punishable the advocacy of overthrowing or destroying the U.S. government by force or violence. In this photo, Rep. Howard W. Smith, for whom the act is named, (D-Va) points to a slogan “You can’t beat Hitler with a 40-hour week,” on Feb. 27, 1942, which he has adopted in his fight to suspend the 40-hour week and overtime bonuses. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Congress has sought to restrict free speech

Regardless of the speech and press clauses of the First Amendment, a Federalist-dominated Congress adopted the short-lived Sedition Act of 1798, which made it a crime to criticize the president of the United States.

Schenck v. United States (1919) is the first case in which the Supreme Court was asked to strike down a law violating the free speech clause.

The issue arose after Charles Schenck published leaflets challenging the conscription system then in effect. The Court unanimously upheld Schenck’s conviction for violating the Espionage Act of 1917 and in doing so established a test requiring a “clear and present danger” for proscribing speech. It applied the Schenck test in Debs v. United States (1919) but applied the less stringent bad tendency test in Gitlow v. New York (1925).

Although the Court generally made the ultimate decision on the constitutionality of congressional legislation, it often deferred to congressional judgments as to which speech constituted a danger. Thus in enacting the Smith Act of 1940, Congress made punishable the advocacy of overthrowing or destroying the U.S. government by force or violence. The constitutionality of the act was challenged in Dennis v. United States (1951), but the Court upheld it by a 6-2 vote, relying on a modified version of the clear and present danger test.

The issue of flag desecration demonstrates the limits of congressional actions. In dealing with a case of flag-burning engaged in as a form of political protest, the Supreme Court in Texas v. Johnson (1989) asserted that the fundamental principle underlying the First Amendment is that government cannot prohibit expression of ideas simply because society may find the idea disagreeable or offensive. Capitol police arrest Scott Tyler, 24, of Chicago after he set fire to an American flag on the steps of the Capitol in Washington Oct. 31, 1989. The Senate was to vote Tuesday, Dec. 12, 1995, on an amendment to the U.S. Constitution giving Congress the power to prohibit desecration of the flag. (AP Photo/FILE/Charles Tasnadi, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Lawmakers have repeatedly tried to prohibit flag burning

The issue of flag desecration demonstrates the limits of congressional actions.

In dealing with a case of flag-burning engaged in as a form of political protest, the Supreme Court in Texas v. Johnson (1989) asserted that the fundamental principle underlying the First Amendment is that government cannot prohibit expression of ideas simply because society may find the idea disagreeable or offensive.

In response, Congress denounced the Court and passed a federal law banning flag burning that the Court then proceeded to strike down in United States v. Eichman (1990). Congress has subsequently attempted to amend the Constitution to prohibit flag desecration, but since 1995 these attempts have failed to gain sufficient votes. The most recent attempt to have an amendment adopted was in June 2006. The measure easily cleared the House, but failed by one vote in the Senate.

At times, Congress has limited the right to petition

The right to petition the government has been interpreted as extending to Congress, the executive, as well as the judiciary. The interpretation of “redress of grievances” has also been interpreted broadly, although Congress has at times directly limited the right to petition.

In the early 1830s, Congress received numerous petitions calling for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. In January 1840, the House of Representatives adopted the so-called gag rule barring petitions for Congress to ban slavery in any state or territory. This standing rule was repealed five years later, in 1845, through the efforts of John Quincy Adams. As a result of the repeal, the House now provides for the acceptance of petitions and has a procedure for entering petitions into the House Journal and publication in the House Record by the Clerk.

Congress nonetheless has in some instances ignored the right to petition over legislation. For example, during World War I, individuals petitioning for the repeal of sedition and espionage laws were punished with imprisonment, with the acquiesce of the Supreme Court. At the time, the Court chose to take no action or judgment to protect individuals’ First Amendment rights under the assumption that it was in the national interest.

CaptionaThere have been times, most notably the McCarthy era of the early 1950s, when congressional actions have appeared to call the right into question, such as when its members held televised hearings into the associations of individuals. Over time, the Supreme Court has made it clear that such investigations must be in pursuit of legitimate legislation.. In this photo, actor Ronald Reagan gives his testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in Washington, D.C., Oct. 23, 1947. The group is conducting an investigation of Communist activities in the film capital. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Congressional investigations during McCarthy era raised questions about right of association

The right of peaceable assembly protects the right of individuals to join, participate in, or organize groups, activities, or gatherings — including political parties, unions, or interest groups — without restrictions from the government. On occasion, however, Congress has attempted to limit the assembly of groups that it considers to be violent.

In United States v. Cruikshank (1876), the Supreme Court held that citizens may “assemble for the purpose of petitioning Congress for a redress of grievances.” The Court in later cases, among them Hague v. Committee for Industrial Revolution (1939), expanded the meaning of the right to assembly to the purpose of communicating views on national questions and for disseminating information.

The right to association allows individuals to mutually choose their acquaintances for whatever purpose they see fit. It is closely aligned with the right of assembly. The Supreme Court derived this right from the First Amendment guarantees of speech, assembly, and petition.

The Court expanded legal protections for the right of association in a series of cases in the 1950s and 1960s involving some states’ efforts to curb the activities of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

There have been times, most notably the McCarthy era of the early 1950s, when congressional actions have appeared to call the right into question, such as when its members held televised hearings into the associations of individuals. Over time, the Supreme Court has made it clear that such investigations must be in pursuit of legitimate legislation.

This article was originally published in 2009. Dale Mineshima-Lowe is Managing Editor for the Center of International Relations, researcher and Associate Lecturer in both the Department of Politics and Department of Geography at Birkbeck, University of London, and Tutor of Politics and History at the City Lit, adult education college in Central London.