The government of the United States, like others, protects against the dissemination of what it considers to be sensitive information. It labels classified documents “confidential,” “secret,” and “top secret,” depending on their level of sensitivity.

Attempting to protect government documents from public view is as old as the Republic.

During George Washington’s administration, the House of Representatives sought to review documents generated during negotiation of the Jay Treaty with Great Britain. Washington responded that such negotiations required secrecy and that public dissemination “might have a pernicious influence on future negotiations, or produce immediate inconveniences, perhaps danger and mischief, in relation to other powers.”

The issue of how the First Amendment protects the dissemination of government documents first came to the Supreme Court in New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), also known as the Pentagon Papers case.

Court rules against prior restraint in Pentagon Papers case

The Court issued a terse per curiam opinion affirming the judgment of two federal district courts that had refused to enjoin the publication of the documents in the New York Times and the Washington Post. The federal government had sought to prevent those newspapers from publishing excerpts because they revealed the secret history of U.S. engagement in the Vietnam War. A former government official, Daniel Ellsberg, had provided the newspapers with the documents. The legality of Ellsberg’s actions was not the issue in the case.

In affirming the refusal to grant an injunction, the Court restated its position in Bantam Books v. Sullivan (1963) — “Any system of prior restraints of expression comes to this Court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity” — and determined that the government had failed to meet that burden.

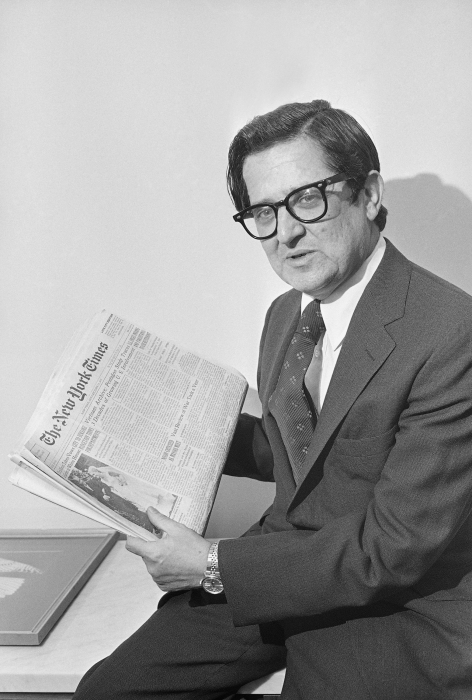

“The press was to serve the governed, not the governors. The Government’s power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the Government. The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and inform the people. Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government. And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell.” – An excerpt from Associate Justice Hugo Black’s concurrence in New York Times Co. v. United States. (AP Photo of Hugo Black in 1970)

The brief per curiam decision was accompanied by six concurring opinions and three dissenting opinions. Justice Hugo L. Black’s scathing concurrence castigated the government’s position. He also disputed the assertion of a majority of his fellow justices that the government could enjoin the publication of classified documents in certain circumstances.

Quoting James Madison, Black argued that it is precisely in the circumstances before the bar, concerning information on why the country had gone to war, that Madison and the framers intended the First Amendment to apply.

Justice William O. Douglas joined Black’s opinion and wrote separately to argue that existing statutes did not give the government the power to exercise prior restraint of publication and that the executive branch had no inherent authority to do so.

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote that the First Amendment was an “absolute bar” to an injunction in such a case. He acknowledged, however, that the case law allowed for some narrow exceptions to the bar on prior restraint of publication.

He cited Near v. Minnesota (1931) to argue that “only governmental allegation and proof that publication must inevitably, directly, and immediately cause the occurrence of an event kindred to imperiling the safety of a transport already at sea can support even the issuance of an interim restraining order.”

Brennan cited as another example an effort to avert a “nuclear holocaust.” Therefore, only if the publication would imperil a specific deployment already in harm’s way would an injunction be constitutional.

In more tempered words, Justice Potter Stewart asserted that in some cases the executive could meet a standard for an injunction, but that it had not done so in this case.

Justice Byron R. White similarly concurred in the judgment, but stated that he did so only because of the exceedingly high burden against prior restraint. He hinted that if Congress had given explicit authorization for a procedure to obtain an injunction, then he might vote otherwise. He also stated that the government could prosecute the offending publisher after the classified documents are published, thus affirming the prohibition of prior restraint, but allowing for other incentives to lessen the likelihood of publication.

Justice Thurgood Marshall argued that the basic issue in the case was the courts’ power to make law in the face of Congress’ refusal to enact that law. No law existed authorizing federal courts to enjoin publication of classified documents, and because Congress makes the law, the courts did not have the power to authorize a prior restraint of publication.

Chief Justice Warren E. Burger and Justices John Marshall Harlan II and Harry A. Blackmun dissented. Burger did not reach the merits but criticized the haste in which the decision was made. Harlan and Blackmun each argued that the government could meet its burden in the case and that each district court proceeding should therefore move forward with the protective stay intact.

Government can stop ex-CIA officer’s proposed book, Court says

A former CIA agent, Frank W. Snepp III was sued by the CIA for not submitting for pre-publication review the manuscript for his book “Decent Interval” about the last months in Vietnam. (AP Photo/Jeff Taylor)

In Snepp v. United States (1980), the Court commented further on the question of prior restraint and classified documents, holding that the First Amendment does not override an employee-employer agreement requiring that a former CIA officer wanting to publish information concerning his activities clear the material with the agency before publication to avoid divulging classified information.

Frank Snepp claimed that none of his proposed book’s contents contained classified information, so he did not need to ask the CIA to approve its contents.

The CIA sued for breach of contract and sought to enjoin further publication, to which the Supreme Court agreed.

Publishing classified information has little constitutional protection

Despite the case of the Pentagon Papers, unauthorized publication of classified documents still receives little constitutional protection outside the context of prior restraint. The government can prosecute people for publishing or otherwise disseminating classified information, and classified documents are exempt from the requirements of the Freedom of Information Act.

The issue of classified documents resurfaced with the George W. Bush administration’s ”War on Terror” following the al-Qaeda attacks of September 11, 2001.

Using the protection that classified documents enjoy, the number of government documents labeled “classified” grew by 60 percent from 2001 to 2003.

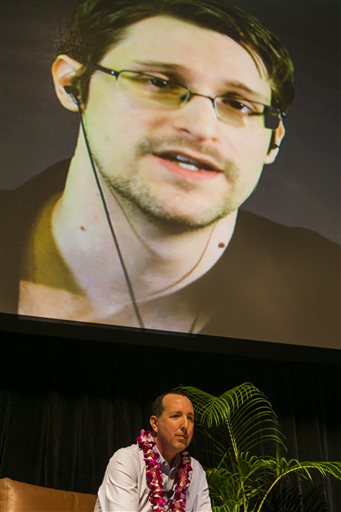

Edward Snowden appears on a live video feed broadcast from Moscow at an event sponsored by the ACLU Hawaii in Honolulu on Saturday, Feb. 14, 2015. (AP Photo/Marco Garcia)

U.S. has prosecuted leakers, publishers of classified documents

Recent years have witnessed dramatic leaks, similar to those involving the Pentagon Papers, and prosecutions.

In June 2024, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange pled guilty to conspiracy to obtain and disclose national defense information in violation of the Espionage Act. The plea brought to an end a long case that started in 2010 when WikiLeaks began publishing classified documents about the U.S. war in Afghanistan and Iraq. Some of the documents revealed the identity of people who were helping the U.S. by passing along information. Other documents reflected poorly on the U.S. operations and exposed a spying campaign on European Union leaders.

Press freedom advocates worried about the use of the Espionage Act to punish publication, outside of punishment for illegally obtaining information, saying that it could have a chilling effect on journalists who receive information to report on national security.

In 2013, Edward Snowden, a systems administrator with access to classified information held by the National Security Agency, leaked thousands of classified documents that revealed that the U.S. government and its allies had been engaged in a massive surveillance program. Faced with possible prosecution under the Espionage Act and possible theft of government property, Snowden fled to Russia, which gave him asylum.

Also in 2013, Chelsea (previously Bradley) Manning, who had served as an intelligence analyst in Iraq, and was the person who had released the flood of documents to WikiLeaks, was prosecuted and received a 35-year sentence. President Barack Obama commuted her remaining sentence in January 2017.

In May 2017 President Donald Trump apparently revealed classified information at a meeting with the Russian foreign minister and ambassador in the White House, but it appears as though he broke no law in so doing. Some scholars have observed that one difficulty of current classifications arrangements is that since the decision to prosecute rests largely with the executive branch, its members can sometimes leak classified information that is favorable while seeking to suppress leaks of such information that is not (Kitrosser 2015).

Justice Department policy limits ability to seize journalists’ records

After criticism over the U.S. Justice Department’s use of subpoenas and other investigative tools to gather journalists’ records during leak investigations, the Justice Department in 2022 updated its guidelines on obtaining information about the news media to prohibit the use of such tools, with narrow exceptions. The policy prohibits the use of a compulsory legal process to gather information from or about a member of the news media who has “in the course of newsgathering, only received, possessed, or published government information, including classified information, or has established a means of receiving such information, including from an anonymous or confidential source.”

The policy shift came after it had come to light in 2021 that the Trump Justice Department had secretly seized the phone records of journalists with the Washington Post, The New York Times and CNN who had reported on federal investigations related to the 2016 presidential campaign.

Leak of secret military information during WWII went unnoticed

The government recently unsealed records from 1942 that indicate that an Australian journalist named Stanley Johnson published an article in the Chicago Sunday Tribune six months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, indicating that the “Navy Had Word of Jap Plan to Strike at Sea.”

In this Dec. 7, 1941 photo made available by the U.S. Navy, a small boat rescues a seaman from the USS West Virginia burning in the foreground in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, after Japanese aircraft attacked the military installation. More than 2,300 U.S. service members and civilians were killed in the strike which brought the United States into World War II. (U.S. Navy via AP)

Knowledgeable readers would have been able to ascertain the Americans had cracked the Japanese code.

Although the government wanted to prosecute him, he does not appear to have realized that the information from which he drew was secret, and there is no evidence that the Japanese read the story or changed procedures as a result of it.

Although the government convened a grand jury, it ended up sealing the information rather than pursuing what Katie Townsend, the litigation director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press says was “the only time in American history that the United States government has . . . taken steps toward prosecuting a member of the media under the Espionage Act” (Quoted in Ruane 2017).

This article was originally published in 2009 and last updated in 2024.