In In re Summers, 325 U.S. 561 (1945), the Supreme Court upheld the decision by the state of Illinois to deny admission of an attorney to the bar because he was a conscientious objector to war. The Court determined that the state’s decision did not deny the attorney’s First and Fourteenth Amendment rights to the free exercise of religion.

Summers refused admission to bar for conscientious objection to war

To be admitted to the bar in Illinois, attorneys were required to take an oath to support the constitution of Illinois, which included a provision requiring service in the state militia during times of war. Clyde Wilson Summers, a conscientious objector and Christian pacifist, applied to be admitted to the bar. The Committee on Character of Fitness of the Illinois Bar, a committee that advises the Illinois Supreme Court on bar admission, “refused to issue a certificate that he was of such moral character as to be allowed to practice law” in the state based solely on his refusal to take the oath.

The Supreme Court of Illinois upheld the finding of the committee, and Summers appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court arguing that the state had violated his First and Fourteenth Amendment rights.

Court upheld denial of admission

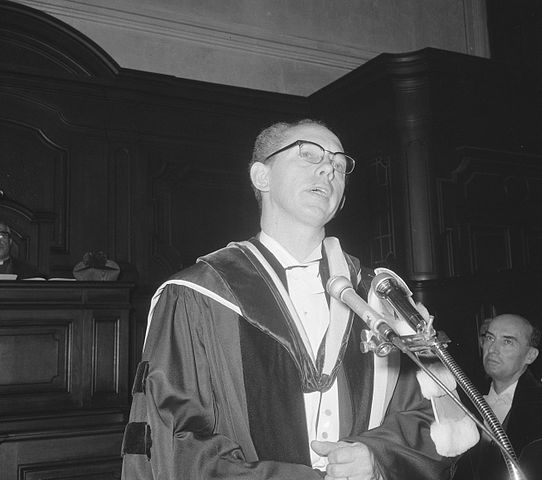

In his majority opinion, Justice Stanley F. Reed first found that because the petition for admittance to the bar was considered on the merits by the Illinois Supreme Court, there was a case of controversy involved and thus the case was justifiable before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Reed next concluded that Summers was not denied due process and that “he was not barred because of his religion but because under the state interpretation of its constitution he could not take the oath of office in good faith.” He further based his opinion on the fact that the Court had previously upheld the denial of U.S. citizenship to immigrants who refuse to pledge military service in an oath similar to the Illinois oath. A similar requirement by Illinois, in Reed’s opinion, was not a violation of the First or Fourteenth Amendments, and the denial of Summers to the bar was upheld.

Justice Hugo L. Black — joined by Justices William O. Douglas, Frank W. Murphy, and Wiley B. Rutledge — dissented, claiming that Summers was denied a license solely because of his religious beliefs. The state agreed that Summers met every qualification, except for the military service provision. This, according to Black, was a clear attack on the religious freedom of Summers, now a professor emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania law school.

This article was originally published in 2009. Jonathan R. Ellzey focused on religion, political behavior, and the judiciary as a graduate student at the University of Florida. He received his law degree from Baylor University and now practices law in Burkburnett, Texas.