The captive audience doctrine protects people in certain places and circumstances from unwanted speech.

Captive audience doctrine is exception to Cohen

The doctrine serves as an exception to the First Amendment rule articulated in Cohen v. California (1971) requiring people exposed to unwanted speech to avert their eyes and ears.

In Cohen, the Supreme Court had refused to permit censorship of an expletive printed on the back of a jacket worn in the public corridors of the Los Angeles courthouse although passersby might be involuntarily exposed to and offended by the message.

Court has allowed regulations to prevent intrusion into homes

The Court has chiefly applied the captive audience doctrine to individuals’ homes.

In Kovacs v. Cooper (1949), the Court upheld an ordinance prohibiting the use of sound trucks, stating that citizens in their homes should be protected from the invasion of “loud and raucous noises” beyond their control.

Although the statute essentially created a regulatory wall blocking otherwise constitutionally protected speech, the Court noted that without the government’s protection, unwilling listeners would be helpless to escape intrusions upon their privacy by messages broadcast from loudspeakers on the trucks.

In Rowan v. U.S. Post Office Department (1970), the Court invoked the captive audience doctrine to uphold a statute permitting individuals, with the assistance of the postal service, to prevent the delivery of offensive mail. Although conceding that the statute impeded the flow of ideas, the Court held that this impediment was subordinate to the right of people in their homes to be free from unwanted material.

According to the Court in Hynes v. Mayor of Oradell (1976), “home is one place where a man ought to be able to shut himself up in his own ideas if he desires.”

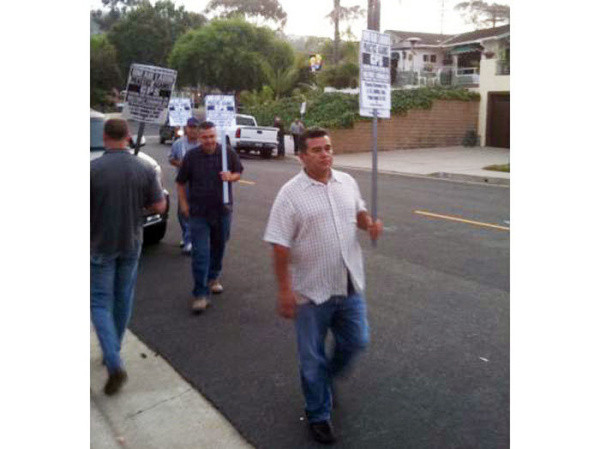

Court upholds restrictions on picketing, adult theaters in neighborhoods

Further expanding on the right of home dwellers to shield themselves from unwanted speech, the Court in Frisby v. Schultz (1988) sustained restrictions on picketing in residential neighborhoods, ruling that protestors had no right to force speech into the home of an unwilling listener.

In upholding a zoning ordinance prohibiting adult theaters from locating within 500 feet of a residential area, the Court in Young v. American MiniTheatres (1976) effectively found that an entire neighborhood constituted a captive audience.

Captive audience doctrine also applied to streetcar riders, minors

The courts have also recognized the rights of captive audiences outside the home to be free of unwanted speech. In Lehman v. City of Shaker Heights (1974), finding that streetcar riders are a captive audience, the Court upheld restrictions on political advertisements played over speaker systems in public transit vehicles. As the Court recognized, individuals riding in a moving vehicle for an extended period of time are unable to avoid objectionable speech.

Lehman stemmed from Justice William O. Douglas’s dissent in the earlier case of Public Utilities Commission. v. Pollak (1952), in which he argued that people should have a right to be let alone from unwanted messages while taking the street car.

The courts have also employed the doctrine to situations involving the exposure of minors to certain types of expression.

When employing the doctrine, the courts elevate the desire of the audience to exclude speech over that of the speaker to convey it, but aside from the few cases in which it has been applied, the captive audience doctrine has not exerted a prominent influence in First Amendment jurisprudence.

This article was originally published in 2009. Patrick Garry, JD, PhD, is a professor of law at the University of South Dakota School of Law. Professor Garry’s books on the First Amendment include Scrambling For Protection: The New Media and the First Amendment, An American Paradox: Censorship in a Nation of Free Speech, and Limited Government and the Bill of Rights.