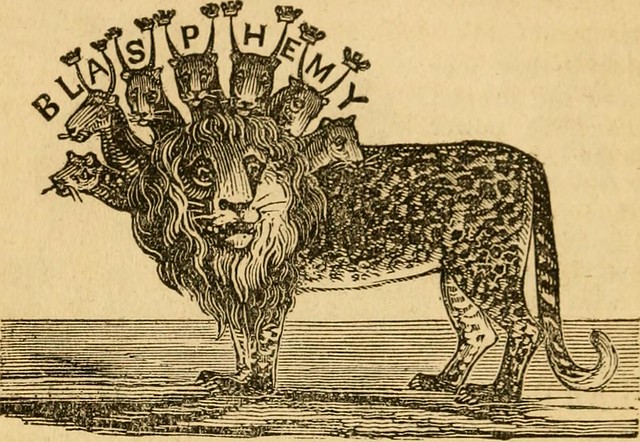

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision in Updegraph v. Commonwealth, 11 Serg. & Rawle 394 (Pa. 1824), reviews a blasphemy conviction and addresses whether American law incorporates British common law ideas that may be in tension with the First Amendment.

Man convicted of blasphemy in Pennsylvania

Abner Updegraph, who belonged to a debating society, had been fined ten shillings under a state law adopted in 1700 for saying that the Bible was full of fables and lies. Writing for the Court, Justice Thomas Duncan did not think the fact that Updegraph had spoken as part of a debating association was a mitigating factor.

Indeed, he feared that the association “would prove a nursery of vice, a school of preparation to qualify young men for the gallows, and young women for the brothel.” Duncan proceeded to address two issues: whether Christianity was part of the common law and whether the prosecution had been properly framed.

In 1824, Pennsylvania Supreme Court upholds blasphemy conviction

in Duncan focused the majority of his decision on the first question, which had divided Joseph Story (who believed that it was) and Thomas Jefferson (who believed that it was not). Although he did not cite these two individuals, Duncan sided with Story. He believed that “general Christianity, is, and always has been, a part of the common law of Pennsylvania.” He was quick to add, however, that this Christianity was a Christianity “without the spiritual artillery of European countries” and is a “Christianity with liberty of conscience to all men.”

Duncan cited James Wilson as stating that “Christianity is part of the common law.” Duncan observed that in 1818 a Mayor’s Court in Philadelphia had upheld a blasphemy conviction against an individual named Murray. Without such laws “every debating club might dedicate the club room to the worship of the Goddess of Reason, and adore the deity in the person of a naked prostitute.”

Court says blasphemy could be prosecuted when it led to breach of peace or provocation

He noted that the laws only punished “malicious” behavior and did not attempt to choose between the doctrines of general Christianity. Blasphemy could be prosecuted either when it led to “an actual breach of the peace, or doing that which tends to provoke and excite others to do it.” Duncan explained that blasphemy laws did not restrict the beliefs of Unitarians or Jews. The intention of the laws was “not to force conscience by punishment, but to preserve the peace of the country by an outward respect to the religion of the country, and not as a restraint upon the liberty of conscience, but licentiousness endangering the public peace.” Thus, the state prosecuted “profane swearing, breach of the Sabbath, and blasphemy” not “as sins or offences against God, but crimes injurious to, and having a malignant influence on society.”

Having thus attempted to prove that the common law included Christianity, Dunan found the specific indictment in this case flawed. Like the law it was enforcing, the indictment should have included the word “profanely”; without it, the conviction could not stand.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.