Public middle- and high school administrators in Wisconsin did not violate the First Amendment by prohibiting students from wearing shirts bearing images of guns, a federal district court has ruled in N.J. v. Sonnabend.

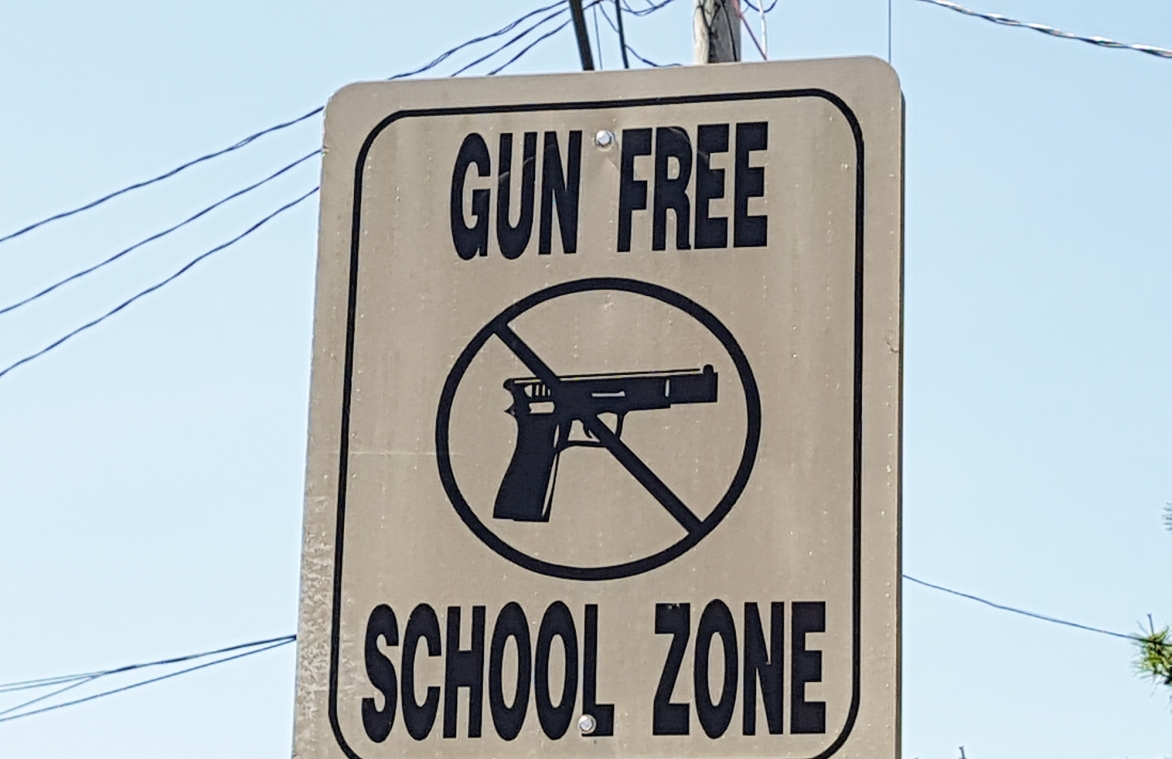

The case involved two students, N.J. from Shattuck Middle School and A.L. from Kettle Moraine High School. N.J. is a gun enthusiast, a supporter of the Second Amendment, and a target shooter. He wore a Smith & Wesson T-shirt with an image of a handgun to school. School officials made him cover up the shirt.

A.L., also a gun enthusiast and Second Amendment supporter, wore a T-shirt with the message “Wisconsin Carry, Inc.” that included an image of a handgun. School officials told him he could not wear clothing with images of firearms. Both schools had dress-code policies prohibiting the wearing of clothing with gun images.

The students, through their parents, filed federal lawsuits, seeking an injunction prohibiting school officials from enforcing the dress codes and allowing the students to wear such clothing. The suits were consolidated.

Shirts are speech

The school defendants initially argued that the First Amendment claims must fail because the T-shirts were not speech within the meaning of the First Amendment. They contended that images of firearms are not inherently expressive.

Under the First Amendment there are certain forms of expressive conduct that are not deemed expressive enough to merit First Amendment review. For example, a federal district court in New Mexico once ruled that the wearing of sagging pants was not expressive enough.

However, here, the district judge recognized that the T-shirts in question were a form of speech, writing that “[a] picture or image of a gun is by its very nature expressive.”

Tinker does not apply

The students argued that the applicable legal standard should come from the Supreme Court’s seminal student speech case, Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969). In that case, the Court ruled that public school officials in Iowa violated the First Amendment when they punished students for wearing black peace armbands, a form of passive political speech that did not substantially disrupt school activities.

The Court in Tinker reasoned that school officials cannot punish student speech unless they can reasonably forecast that the student speech will cause a substantial disruption, or material interference with school activities, or invade the rights of others.

The Tinker case also involved what is known in First Amendment law as viewpoint discrimination—the government favoring the viewpoints of certain private speakers over others. That applied in Tinker because the school disallowed the wearing of the black armbands but allowed students to wear other symbols, such as Iron Crosses or political-campaign buttons.

However, the federal district court in the Wisconsin T-shirt case determined that Tinker did not apply to restrictions on student speech in a non-public forum when the restrictions are viewpoint neutral. The district court said schools are non-public forums when class is in session. Furthermore, the district court reasoned that the restriction on images of firearms applied whether or not the images were pro-gun or anti-gun.

Court applies a Hazelwood-type standard

Instead of applying Tinker, the judge applied a version of the standard articulated by the Supreme Court in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988), a high school press-censorship case. In Hazelwood, the Court ruled that with regard to school-sponsored student speech, public school officials can restrict student speech if they have a legitimate pedagogical or educational reason for doing so.

In this case, the district court applied a similar type of standard. The school defendants argued that the prohibition of clothing with firearm imagery is justified because many students expressed fear and anxiety about images of guns. In December 2019, a student in nearby Waukesha had brought a gun to school and fired it at a classmate.

“Although it is true, as Plaintiffs emphasize, that mere images of firearms cannot inflict injury on anyone, the image of a firearm on a classmate’s shirt in the school environment can be a reminder of the school violence that lies at the heart of the schools’ concerns,” the judge wrote.

Because of these concerns over school shootings, the judge wrote, “Defendants’ decision to prohibit students from wearing clothes with images of firearms was not unreasonable.”

The judge also reasoned that students can still express their support for firearms in other ways. The judge said the students “even remain free to wear shirts that express their support for the Second Amendment [right to keep and bear arms] in other ways.”

The district judge also cited another legitimate educational reason—the so-called “weapons effect.” The court explained: “The weapons effect is the name given to the theory that the mere presence of guns or images of guns increases aggression in people.”

Plaintiffs argued that images of guns do not increase aggression, but the school defendants had introduced the opinion of a psychologist who wrote that images of guns at school can increase aggression in students.

The district judge noted that the school defendants’’ interest in “reducing student aggression” was a legitimate pedagogical goal.

The court concluded that the school defendants had legitimate educational reasons to implement the ban on images of firearms at schools.

The Free Speech Center newsletter offers a digest of First Amendment and news media-related news every other week. Subscribe for free here: https://bit.ly/3kG9uiJ

David L. Hudson Jr. is a professor at Belmont University College of Law who writes and speaks regularly on First Amendment issues. He is the author of Let the Students Speak: A History of the Fight for Free Expression in American Schools (Beacon Press, 2011), and of First Amendment: Freedom of Speech(2012). Hudson is also the author of a 12-part lecture series, Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (2018), and a 24-part lecture series, The American Constitution 101 (2019).